Trout Streamings!

June 17, 2023

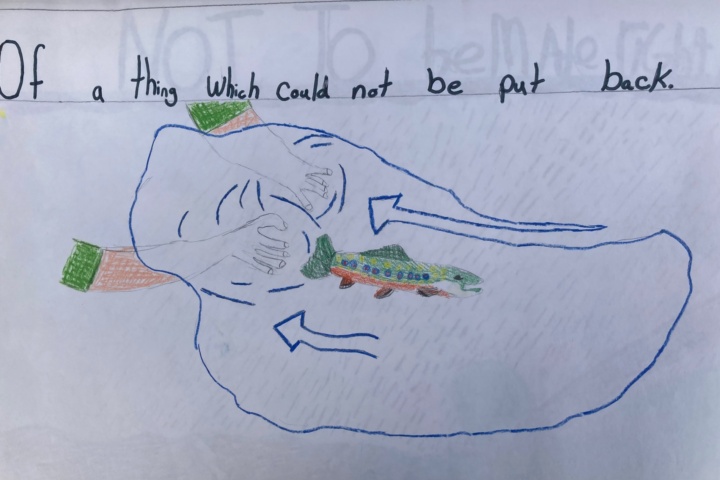

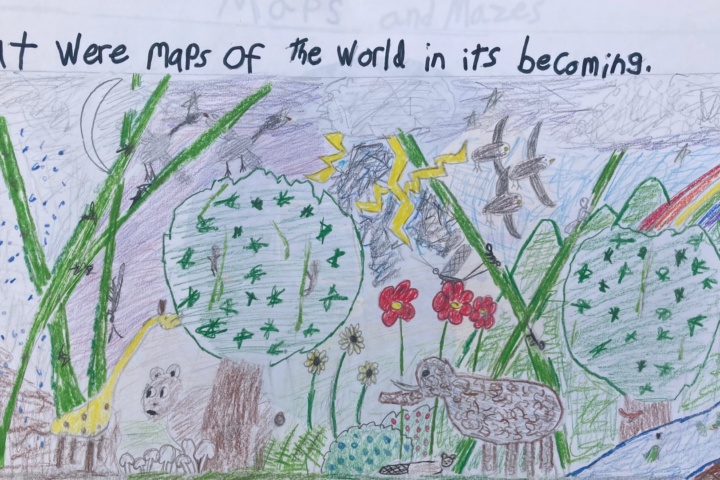

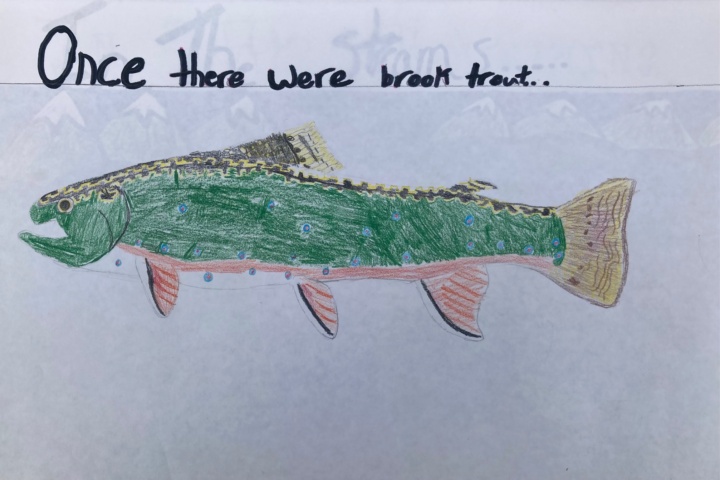

Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains.

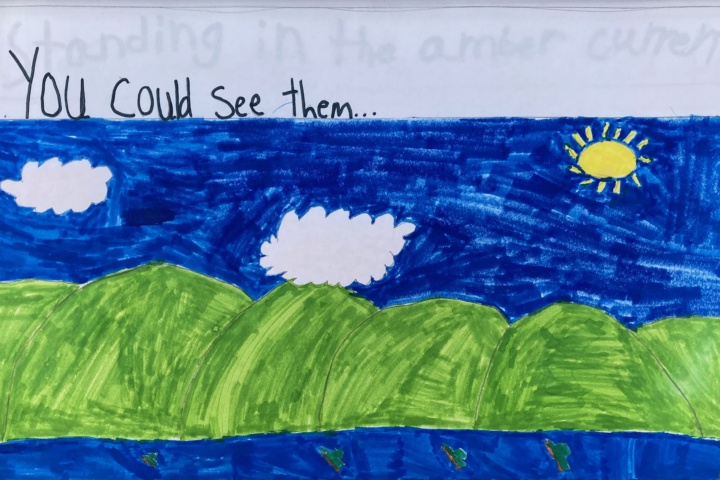

You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow.

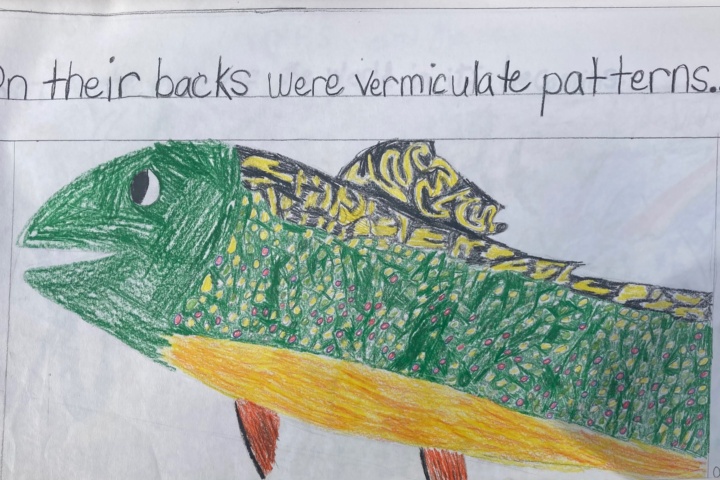

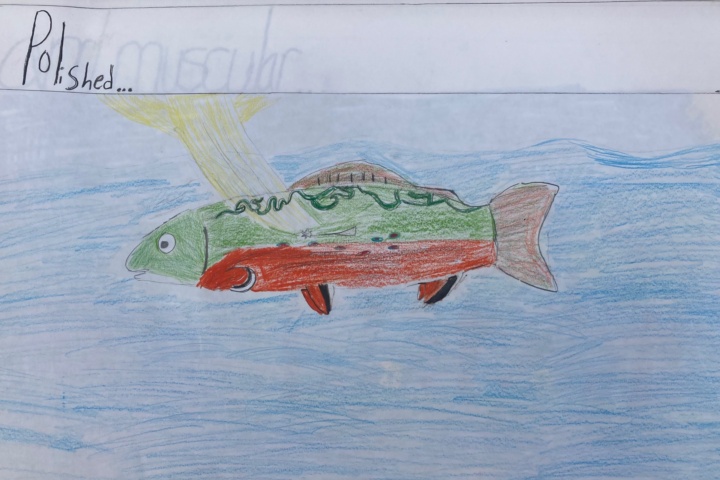

They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional. On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming.

Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.

June 14, 2023

Many more Release Day photos! Thanks for those submissions.

VSNB

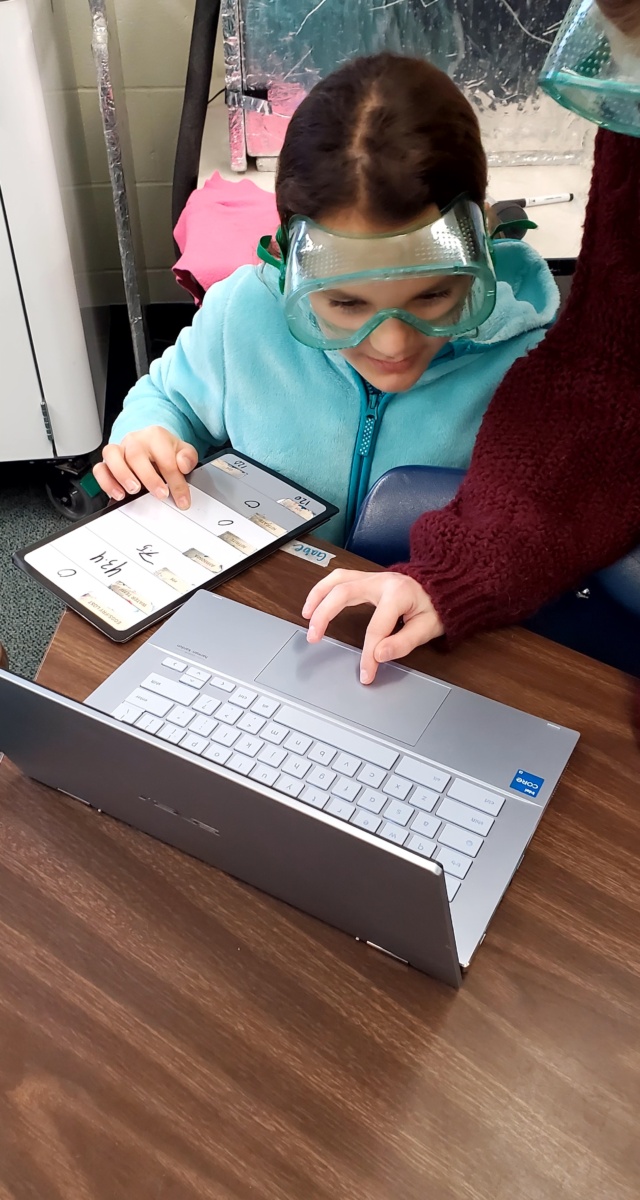

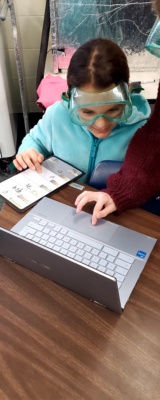

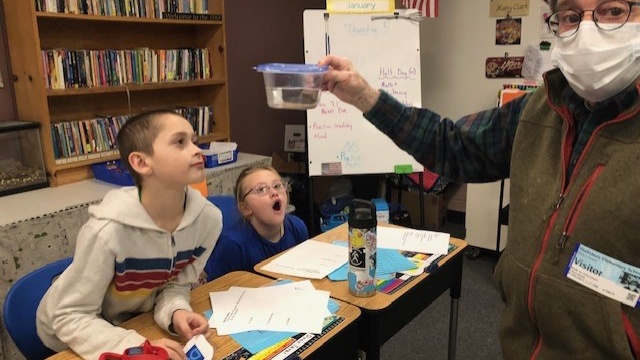

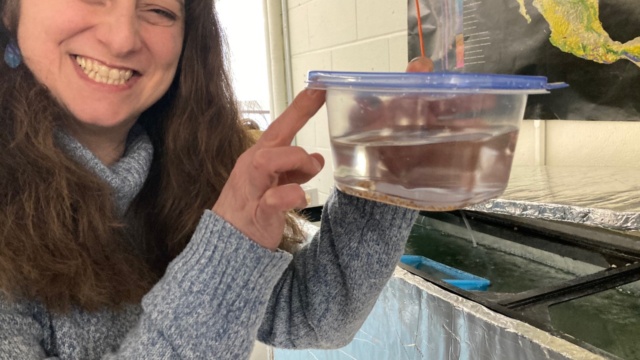

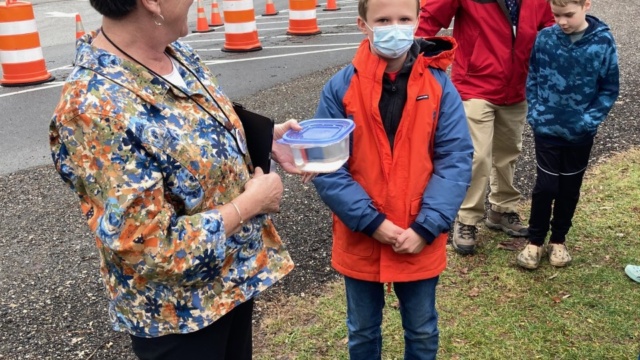

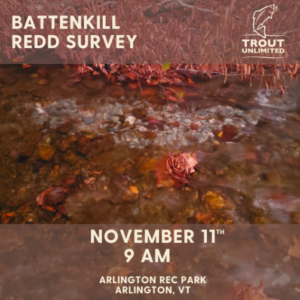

The Village School of North Bennington had a great Release Day in spite of the drizzly weather. Teacher Sam Coulter and her students were joined by TU volunteers Barry Mayer, Bonnie Daley, and Erin Lyons. Also participating in the release were the head of school and the librarian, who previously ran the TIC program.

The students released their fish into nearby Paran Creek, which has the distinction of having produced, in 1977, Vermont’s largest recorded brook trout. The headwaters of Paran Creek may now be threatened by a proposed 85 acre solar array.

Volunteer Bonnie Daley offered these thoughts on the day.

What a fun time on the stream with Sam’s VS sixth graders. I really enjoyed watching their enthusiasm and joy observing macroinvertebrates and releasing the little brookies. Here are some pictures I took. Thanks,

MEMS

In gorgeous weather, Melissa Rice, legendary Manchester Elementary and Middle School teacher who retires this year, led her students in her tenth and final Release Day on White Creek in West Rupert. Melissa chose White Creek as her release site because it is a few yards from Lang Brook, where Trout Unlimited is engaged in stream habitat improvement projects. Melissa and her students had visited the spot earlier in the spring to learn about TU’s work, which involves constructing “beaver dam analogs,” known in the literature as BDAs, Here’s an explanation of BDAs and how they work.

Melissa’s class was joined by Jacob Fetterman, head of the Battenkill Home River Initiative project and Erin Rodgers, TU scientist working in western New England (click on their names to read stories about Jacob and Erin). Also along on the outing, which included collecting macroinvertebrates, drawing maps of the area, and a stream study activity, was Pete McCostis, who will take over TIC from Melissa next year.

Here are a handful of photos of the day.

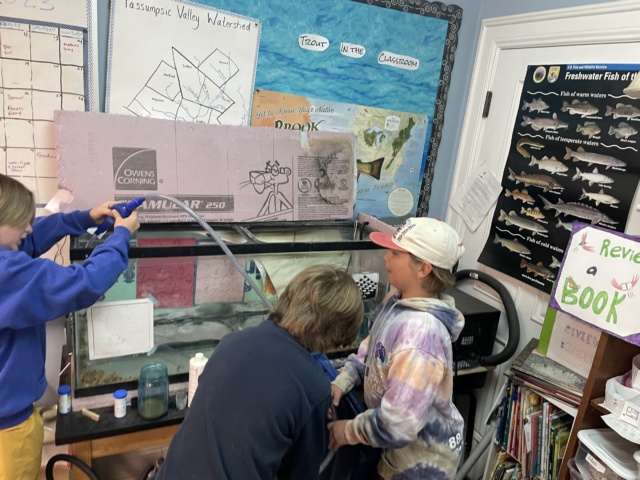

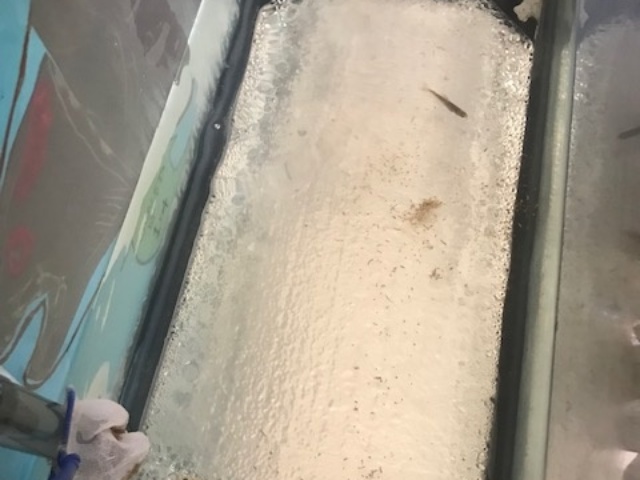

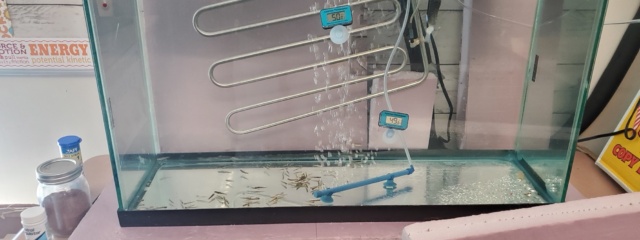

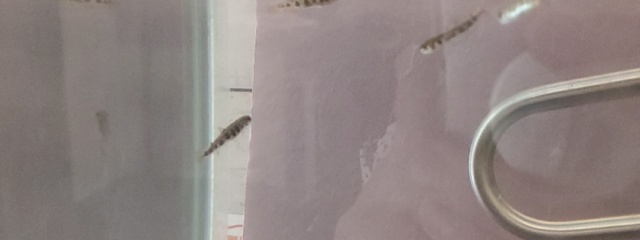

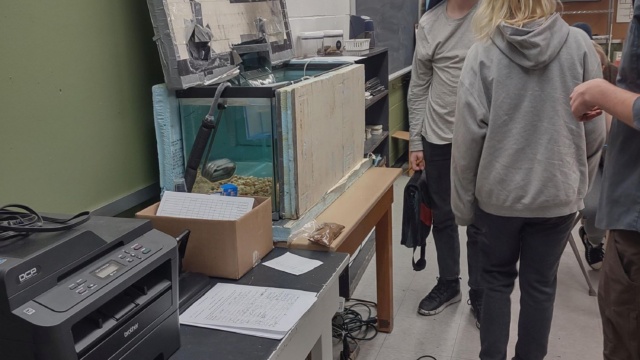

Wallingford Elementary School

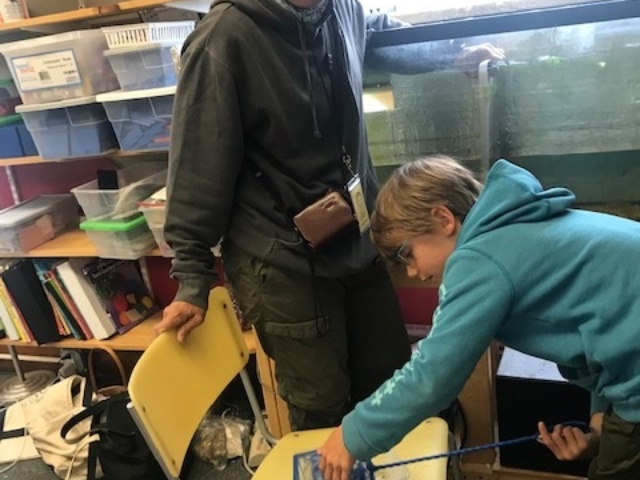

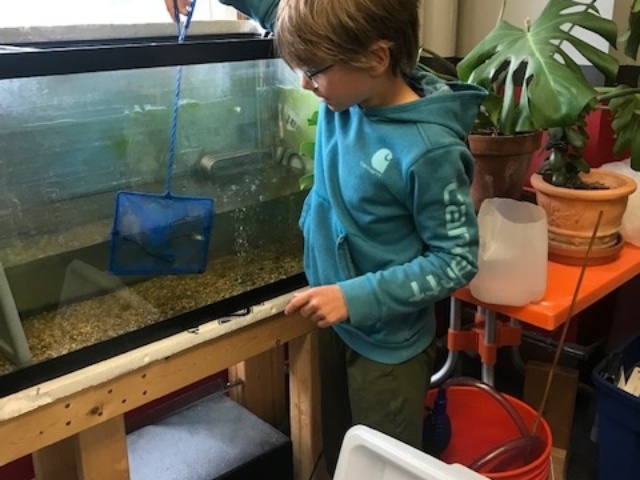

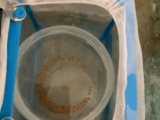

Here’s what the WES trout looked like the morning they were about to be collected to take them to their release site.

First-year TIC teacher Barb Nauton held her release on Roaring Brook in East Wallingford. She was assisted by former WES TIC teacher and now retiree Pat Bowen. Trip Westcott and Tom Culvert led a casting session. Two Fish and Wildlife staff, whose names I didn’t get, electrofished the brook–always popular! I worked with the students to collect and classify macroinvertebrates.

Ludlow Elementary School

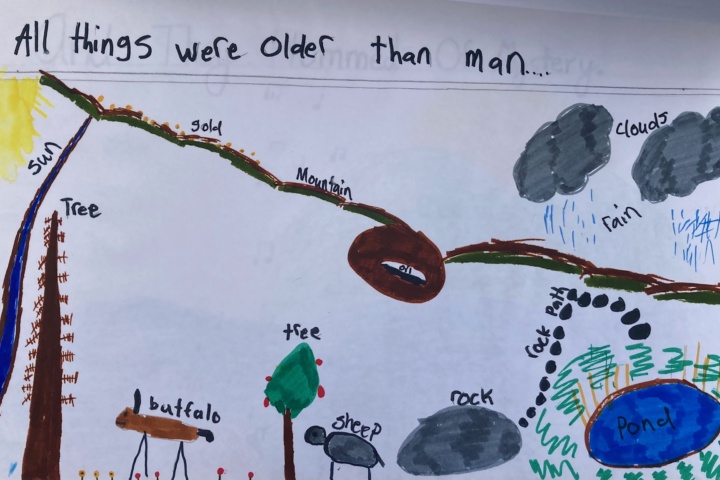

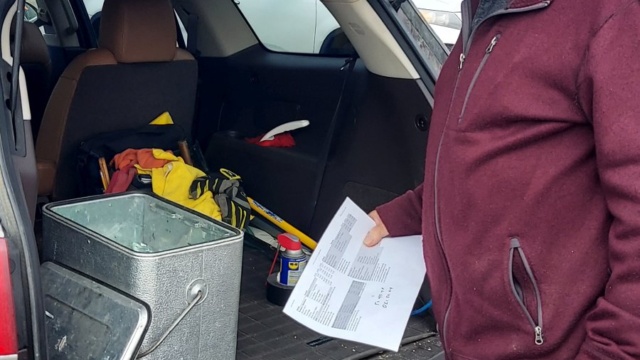

When the WES school bus pulled out of the driveway after the Wallingford release, I quickly made a lefthand turn to drive over the ridge on my way to Plymouth, where Lisa Marks and her students were waiting for me to join their release on the Black River. Lisa had arranged for me to meet WCAX reporter Joe Carroll, who wanted to interview me. He did that while the kids had lunch. Lisa’s students had also prepared a giant banner covered with their trout artwork.

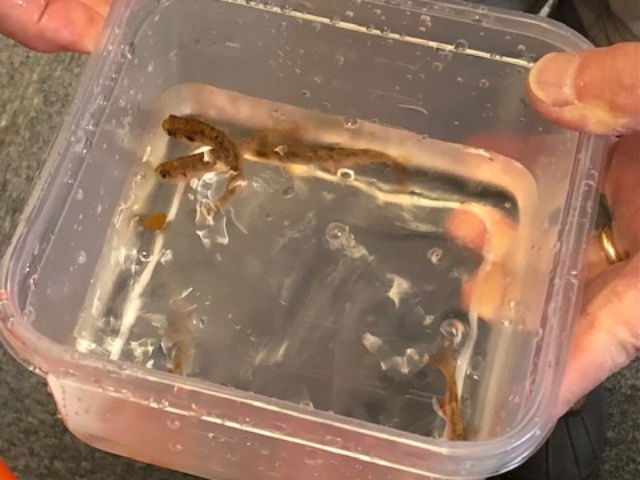

During our macro collecting activity, one of Lisa’s students found a classic case-builder caddis larva. Gorgeous!

Central Vermont Career Center

Ari Lattanzi, of CVCC, sent me these three videos of her release of their 85 fry (!) into Jail Branch. Thank you, Ari! I almost feel like I was there streamside with you and your students as you released your fish.

Thank you, Ari!

The Riverside School

Hanna Galinat of The Riverside School provided this report:

We had a successful release–sending roughly 80 trout into the Passumpsic River at Kingdom Trails in East Burke. We also released wooden boats we had carved, similar to Paddle to the Sea. We enjoyed a talk from Clark Amadon from Mad Dog TU and sampled for benthic macroinvertebrates–finding many caddisflies, mayflies, and stone flies.

Here are some photos from Hanna’s Release Day.

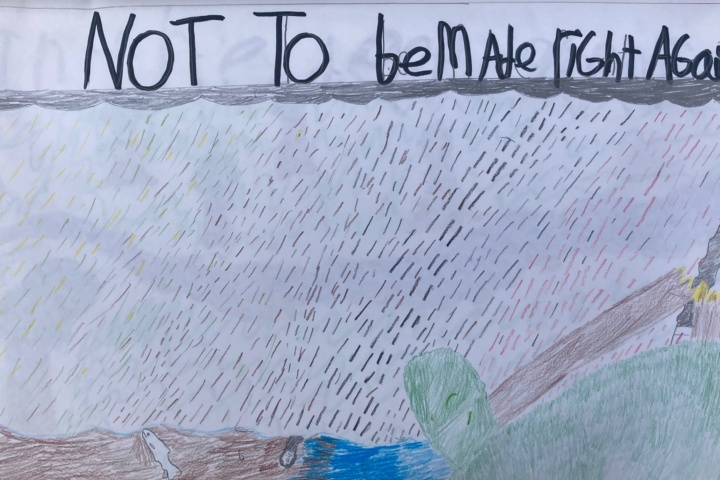

Mount Anthony Union Middle School

MAUMS wasn’t as fortunate weather-wise as many schools were this release season, but the rain that fell was lighter than predicted. Emily Hunter organized a six-station plan that kept her 76 seventh graders busy and learning both on the MAUMS campus and at Furnace Brook, which her classes can walk to. She was assisted by TU volunteers Bonnie Daley and Barry Mayer, among others. Here are photos that Bonnie and Barry took that day.

Neshobe Elementary School

Neshobe is another TIC school that has the good fortune of being able to walk to its release site, the Neshobe River just upstream from the school. Teacher Kim Faber led her students to the river while her helpers deployed to their stations. Since I was leading the macroinvertebrates activity, I didn’t know what all of the helpers were teaching the kids, but I was aware that retired Rutland High School history teacher John Peterson, who came in 19th Century garb, had positioned himself next to an abandoned forge to introduce Neshobe’s students to the important history of Brandon’s iron industry. Kim conducted the release. Here are some pictures I took of the day.

May 20, 2023

First Release Day photos and reports! How to net your fish and transport them to the river. End-of-year clean-up.

Our normal advice about when to release your fish is during the last two weeks of May and the first two weeks of June. Well, we’re there, and some of our Vermont TIC fry are now adapting to their new watery homes.

Otter Creek Academy release

One of the first reports I got was from Brian Crane, principal of Otter Creek Academy. Here’s some text he shared with the OCA community.

On Thursday, we had our culminating event for Trout in the Classroom. We released 66 Brook Trout into the approved location of Sugar Hollow Brook. Since they arrived as eggs in January, we lost a little over 30 for different reasons. This is totally normal and the fish we released were very healthy and VERY big for their age.

This program was so much more than a single release. We began learning about Brook Trout back in the fall. As a school, we learned about trout anatomy, diet, and habitat. We did many activities as a school and implemented a big buddy/little buddy program we called “Trout Buddies”. Teachers took the idea and ran with it in their classrooms. For example, Ms. Kimball produced and directed “The Trout are in Trouble” for her grade one students. Our release was a day of learning with several stations on the river and a great tour of the Eisenhower Fish Hatchery.

This program was intended to bring us together as a school and promote our vision of a nature-based and experiential learning school. It was a true team effort that paid clear dividends.

Brian posted this message along with photos of the school’s Release Day on his Principal’s Page. Here’s a slideshow of the day’s activities, both at the beautiful Pittsford Recreation Area and at the Eisenhower fish hatchery.

But it’s also a bittersweet season

As exciting and fun as Release Day is for most schools, it can be a bittersweet time too for a couple of reasons.

For one, every year a few schools lose all their fish and have nothing to release. (They could, of course, still spend a few hours at the brook where they had intended to release the fry and do everything else. e.g., collect macroinvertebrates, study the stream’s characteristics and habitat, play “Macro Mayhem,” etc.). Sometimes it’s obvious why all the fish died, but every year we’re left with at least a couple of mysteries. The teacher and the students seem to have done everything right, and yet there was a massive die-off. At best, we have hypotheses and guesses about what might have gone wrong, but it’s frustrating not to have a definitive explanation.

The other cause of bittersweet feelings is just the fact that, after living with and caring for these increasingly beautiful creatures for six months, we miss their presence when we return to the classroom on the first school day after their release.

All in all, 2022-2023 was a very successful year for our Vermont TIC schools!

End-of-year clean-up

One way to distract yourself and your students from those sad feelings is to dive into the process of cleaning the tank and its equipment and packing it away until next year. (See Chapter 10 of the Manual.) It’s so much easier to clean the TIC components now rather than waiting do it in November after the grime and calcium have been able to harden in place for half a year.

While most Vermont TIC schools have what are called “drop-in” chillers (which are easy to clean by a process described in the Manual), some have “flow-through” chillers. These pump water out of the tank and through a mini-refrigerator and then back into the tank. Cleaning these requires a different process, which you’ll find described in this document.

St. Johnsbury School Release Day.

Susan Torres, of SJS, offered this reflection on a challenging but ultimately quite successful year.

Ok. I did not want to respond sooner and jinx myself like I did when Andrew asked everyone how things were going with Swim Up. It was like a “rebirth” after almost two weeks of looking like a tank of dead fish, but not dead because they would still twitch when the water was agitated.

I spent a small fortune on chemicals to try and stabilize the water. It never went back to what I would consider great, but I stopped after a few days of not having a pile of fish on the bottom. I wanted to leave well enough alone. Nothing changed to make me start testing or using chemicals again. I try to do a hands off approach unless needed because that has worked well over the years.

Today, we released 64 trout! Though this is the lowest number I have ever released, at one point I didn’t think I was going to have any survivors, so I’ll take it. Some were even getting “big,” “cute,” and what I might consider chubby. As I was starting to take water out of the aquarium to make it easier to catch them for their release, a dead fish got lifted off the bottom of the aquarium and one of the fish about halfway up started eating it! It was so cool to see! Before we could get a picture or the kids could see it, it let it go.

Thank you for all of your help!

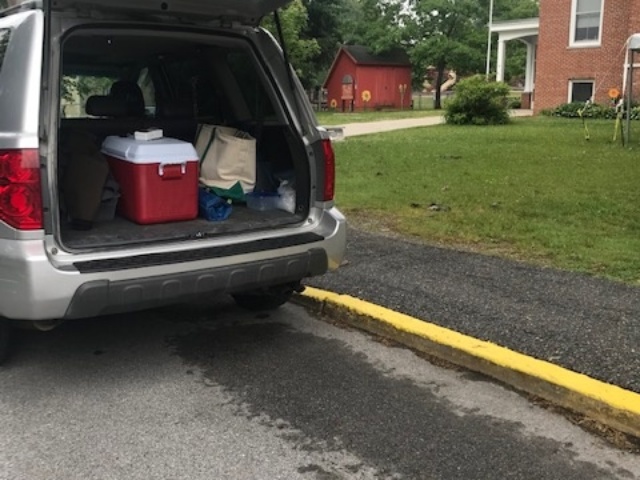

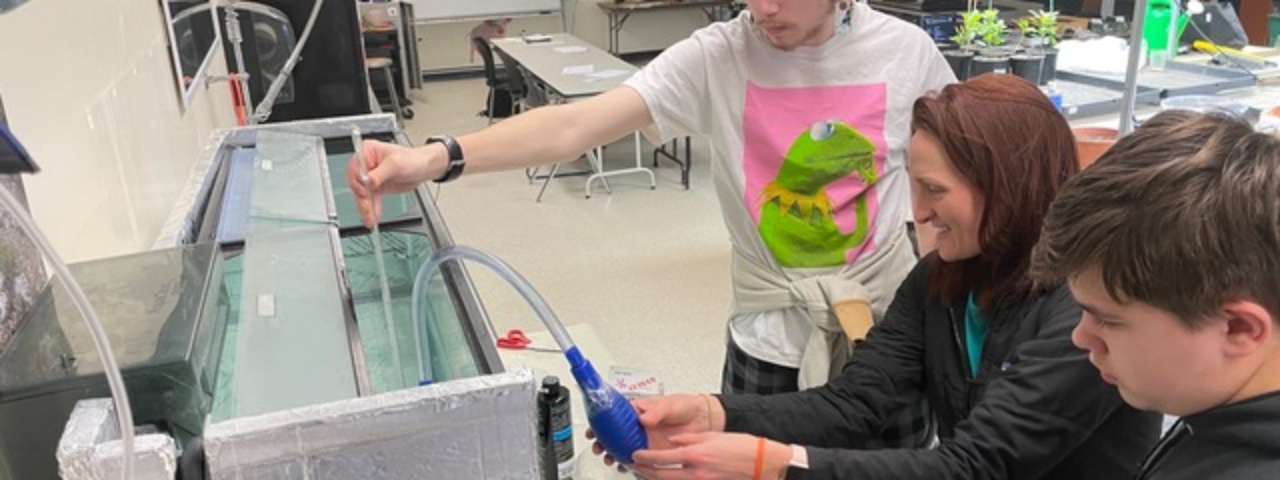

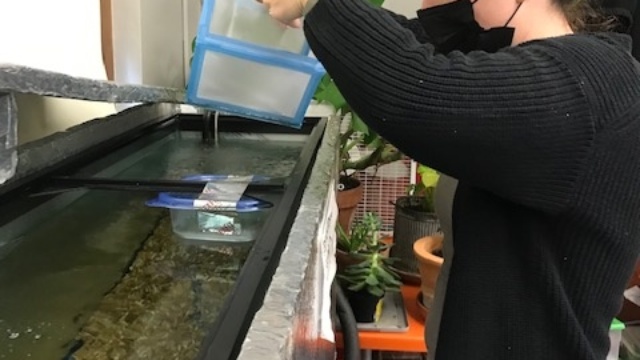

How are you going to get your trout to the stream?

Depending on how far you have to travel and how much time will transpire before you actually release your fry, a container for transporting your fish to the release site might be very simple or a bit more complicated.

If your target stream is only 15 or 20 minutes away AND you plan to release your trout soon after arriving at the stream, you can probably use a conventional 5-gallon bucket (with top). If it’s a hot day, you should probably freeze a couple of plastic bottles of tank water and add those to the bucket when you’re worried that the water temperature may be rising.

But depending on distance and other factors, it may be desirable to transport fish in an aerated cooler. That way, you would also have the option of releasing your trout at the end of a couple of hours of in-stream fun.

Here are instructions for modifying a standard 48-quart cooler for use on Release Day. (This could be done more simply, but I chose to take an approach that would allow our family to still use the cooler for picnics.) Here are photos of the modified cooler, which provides for a battery-powered aerator and a way to install you digital thermometer so you can monitor the water’s temperature.

You can also find a commercial version of this DIY fish transporter that looks like this. (Click on the image to go to the Amazon web site.)

The third video on the Release Day Videos page (available here) shows an example of how former Mary Hogan School teacher Steve Hogan creatively found a way to keep his trout in the stream for hours by fastening netting inside a milk crate. That’s a great way to do it!!

And read Chapter 9!

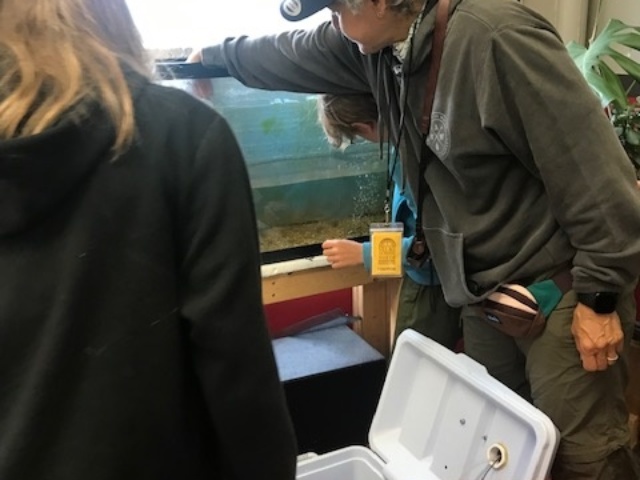

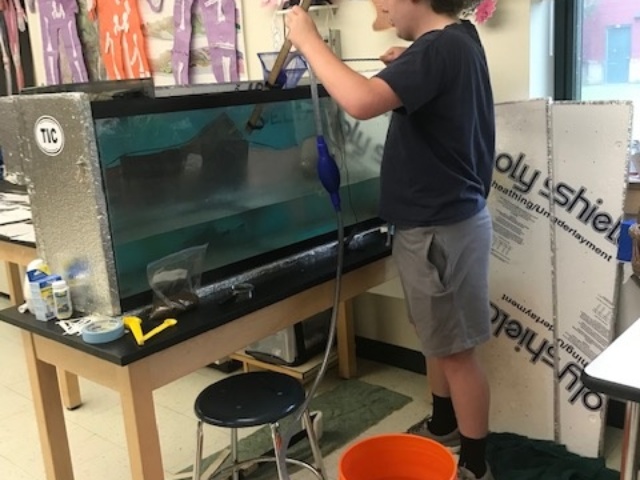

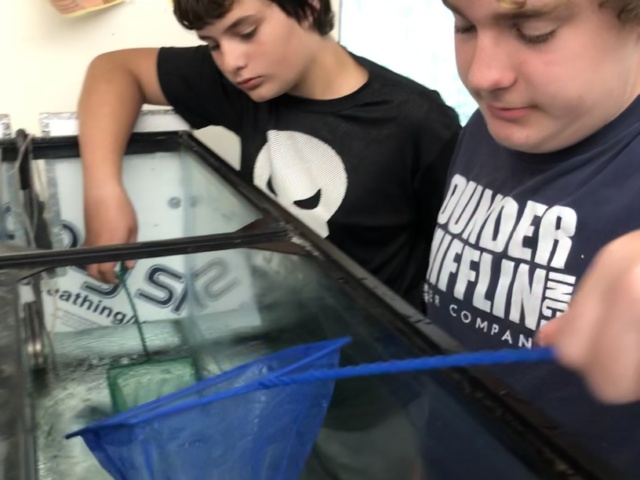

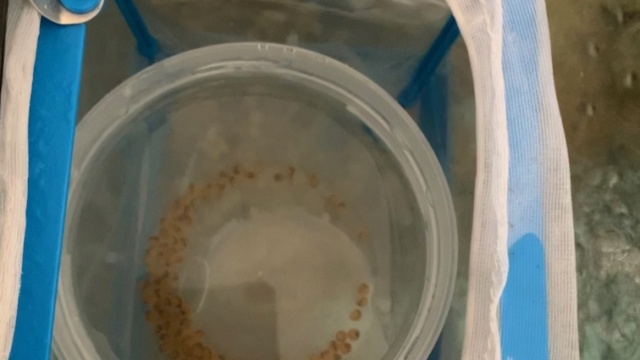

Catching your fish so you can take them to your Release Day event

In Susan Torres‘ statement above, she talks about removing water from the tank to make it easier to net her fish. In fact, catching your trout to put them into the transport container can be surprisingly challenging. The first time you dip your net in the tank, you’ll probably catch quite a few; but, with each successive attempt, the fish will become more and more skittish and better at evading your net.

Here’s some advice for how to make the tank-to-cooler transfer.

- Ideally, at least four people will collaborate on this project: two, the wranglers, will work together to net the fish and put them into a third container; then the other two, the counters, will count the new additions and transfer them to the cooler or bucket you’ll be using.

- Ideally, you will have two nets, one large and one small (photo below).

- Turn off the chiller, filter, and aerator and remove them from the tank. (Also remove any rocks or tank “furniture” you may have added.)

- Use a ruler or other straight-edge to push gravel down to one end of the tank.

- Remove half of the water from the tank.

- Add some of that tank water to your transport container (if you’re using a cooler, fill it about 1/3rd full; if you’re using a bucket, fill it about half full).

- Start out with several cups of water in your third container.

- The fish wranglers should net several fish (any number up to about seven–more than that will be hard to count), put them into the third container, and hand that to the counting team. (Having two “third containers” would expedite the process.)

- The counters should count the new additions, record that number on a whiteboard or clipboard, pour the new fish into the cooler, put some cooler water back into the third container, and hand that container to the wranglers.

- Keep netting and counting.

- Netting the last fish–those little doggies!–can be challenging. The wranglers will have to work together, sometimes “driving” the last holdouts toward the big net. (Depending on the eyesight of the wranglers, they may want to give their nets to those with more acute vision.

- Even when you think you’ve got them all, check again, and again. There’s often at least one small fry hunkering down in the gravel. Stirring the gravel up a bit may allow you to spot them.

- If there’s any chance of water in the cooler sloshing around on the trip to the river, strap the cooler closed or fasten it with rope or duct tape.

April 30, 2023

Wildflowers! TIC in NYC. How are our salmonids doing? Log drives of yore.

The beauty of spring wildflowers.

This is a great time of year to send your students outside looking for wildflowers. In Rutland County, where I live, many flowers have already emerged in the woods and fields and along the streams, with many more to come. In northern areas and especially up at higher elevations, the bloom will happen a bit later. Here’s a slideshow of five of the first species I was able to photograph.

Trout in the Classroom in the Big Apple.

Somewhat surprisingly, one of the oldest and certainly the largest TIC program in the country is in New York City. Approximately 10,000 students benefit from this terrific environmental education curriculum every year.

Some background. Before there was TIC, there was SIC. Trout in the Classroom is an adaptation of Salmon in the Classroom, initially called Fisheries in the Classroom, which started on Canada’s Pacific Coast in the 1970s. Eventually, SIC traveled south and, by the 80s, could be found in numerous western U.S. schools. Finally, in 1991, it leapt the country and, thanks to an enterprising New Jersey teacher, reached the East Coast, where the species of choice became New Jersey’s state fish, the brook trout. It didn’t take long for TIC to cross the Hudson River and establish a foothold in NYC. With strong support from New York’s Department of Environmental Protection, TIC grew rapidly in the metropolis. Unfortunately, unlike in Vermont, very few New York kids have the opportunity to encounter, much less explore, a trout stream. For these students, their one and only forest outing was probably the result of a two and a half hour bus ride.

Those of us privileged to live in the Green Mountain State are so fortunate! Click on the image below to access the full article.

How are our trout and landlocked Atlantic salmon doing?

I don’t get as much feedback on the progress of our tanks and fish as I would like. Here’s some of what I’ve heard:

- A few teachers have had high rates of die-off, in at least one case, complete die-off. (That school isn’t far from the Eisenhower hatchery, so I contacted the hatchery manager there to see if I could get some replacement fry. Guess what? They had had high die-off too so were not in a position to give me some of theirs.)

- Quite a few have reported lower than average mortality rates to date.

- Some schools report very big fry so much so that the teachers are considering moving Release Day up. My advice: that’s probably not necessary unless you have persistent ammonia and/or nitrite problems that you can’t control with siphoning and water changes (and more NiteOut II).

- Unprecedentedly, one of our schools was placed on lockdown for several days. The teacher was concerned about her fish and wondered how long they could survive without feeding. According to our TIC Manual (page 36), “Trout can survive a 10-day vacation without food or water changes.”

But let me hear from you. How are your trout doing?

\

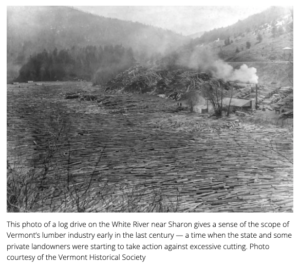

The log drives that scoured our rivers

Today’s VTDigger ran an article by Mark Bushnell on a topic I’ve discussed before in this blog: the massive annual log drives that transported the bounty of Vermont’s forests to ports and markets downstream. One of the details in this interesting piece is that in the last major drive on the Connecticut River in 1914-1915, the bank-to-bank jumble of timber stretched from Barton to Bellows Falls, a distance of 80 miles! Can you imagine the damage these drives to Vermont’s riverine environment? Mark also describes the risks involved for the 2,000 men hired to conduct this drive. Click on the photo below to go to the story.

Let’s hear from you.

April 11, 2023

Fish photos and videos, stream temps, blog contest for kids, macros on Release Day, Earth Day!

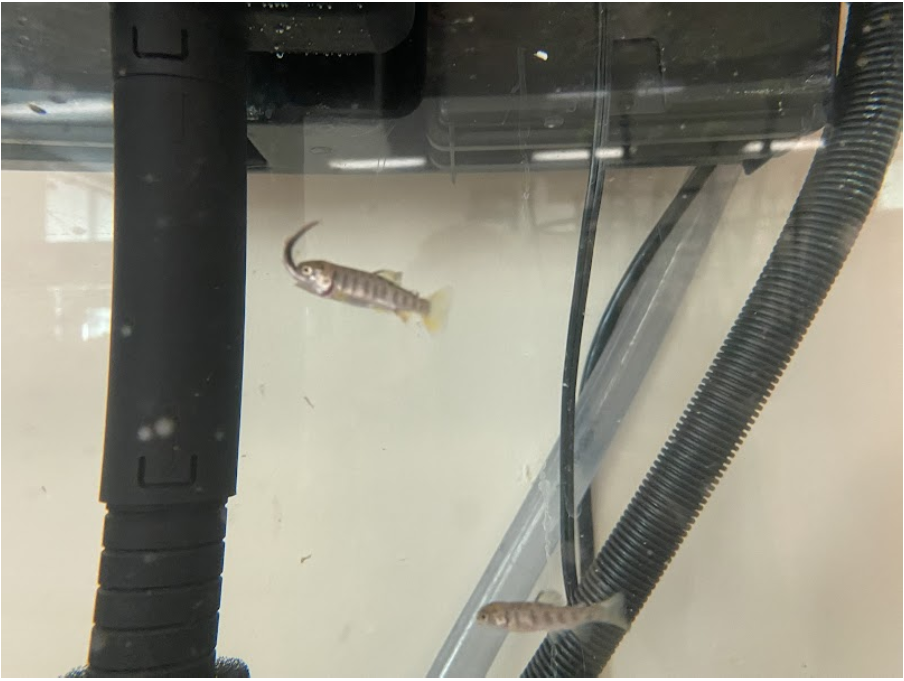

Ariel Lattanzi’s fish

TU volunteer Clark Amadon sent me this photo of the beautiful fish at Central Vermont Career Center. Look at those colors! You and your students are doing a great job taking care of your fish, Ari!

Maple Street School trout

And here’s a short video that Suzanne Alfano, of Maple Street School, sent me. Lots of schools, but not all, seem to be having a good TIC year.

Update on stream temps

I live within walking distance of the Castleton River (see below), so at this time of year, I often go down to the stream to drop my thermometer (on a 25′ string) off a bridge over the river. I did that on 3/30–the water was 39 degrees. I did it this past Friday, 4/7–the temperature was 39. And I did it again yesterday–the water was up to 48 degrees. Given that the air temperature is meant to be 81 this Thursday and 78 and 75 the days after that, I expect the Castleton River to be in mid-50s very soon.

Now, this part of the state is considered to be “The Banana Belt,” so your rivers might very well be much cooler. But urge your kids to get out there and start monitoring the local streams.

One of the other things I’ve learned by often measuring stream temperatures is that when you take the temperature matters. If you take the temp at 8:00 am after a cold night, the temperature might be six or seven degrees cooler than it will be at 6:00 pm after a warm, sunny day. Here’s what the river looked like this afternoon.

NPR Student Podcast Challenge

I just learned about National Public Radio’s Student Podcast Challenge. Unfortunately, the deadline for entries is April 28, so there’s not a lot of time for students to decide to participate and then produce their podcasts.

Click on the image above to go to the contest’s home page, where, among other tips, you’ll find out how making a “pillow fort” can make your voice sound better.

Some key rules:

- Podcasts must be at least 3 minutes long and no longer than 8 minutes.

- Podcasts must be created by students but must be submitted by an educator.

- Judging will occur in three categories: grades 5 through 8, grades 9 through 12, and college.

Here’s a link to all the contest rules.

It’d be great if some of our Vermont students put together podcasts on trout or a trout-related theme. I’d certainly try to find a way to embed it/them into this blog.

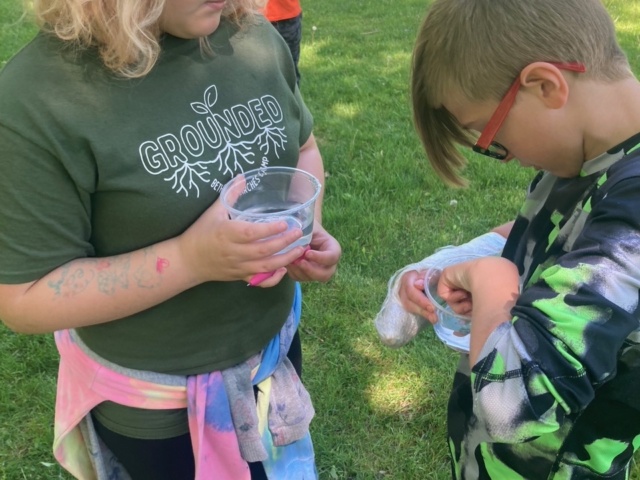

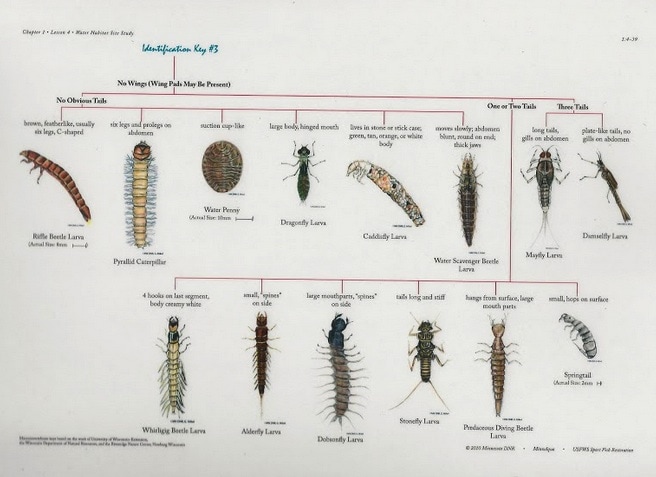

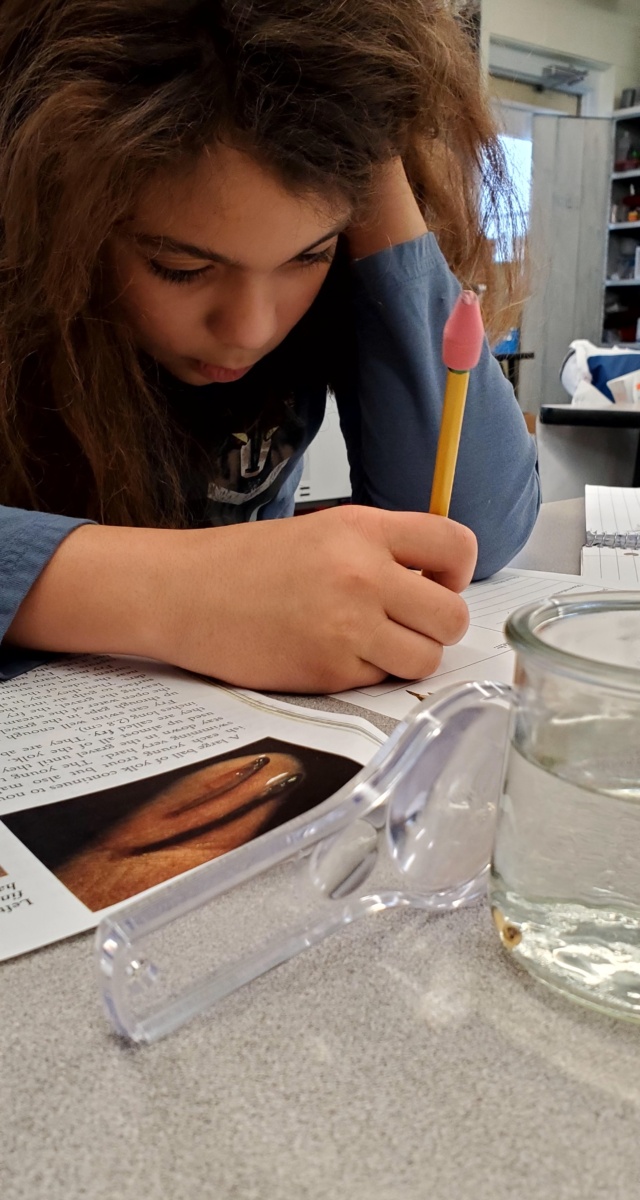

Collecting macros, including on Release Day

In my last blog I mentioned that one activity that lots of teachers and students especially enjoy is collecting and classifying macroinvertebrates.

Many TIC programs engage their students in stream studies, both during the school year and on Release Day. One of the most popular in-stream activities is collecting and classifying macroinvertebrates and then using the macro data to calculate the stream’s “biotic index,” a measure of its health.

To collect macros, a net of some sort is needed. Commercial nets–usually a rectangular or D-shaped net attached to a long handle–are available but can be expensive. I’ve provided links below to two examples, one (a “student” version”) costs $34.60, the other, (probably designed for professionals) costs $276.

But “kick screens” are also easy and inexpensive to make. All you need to do is buy a six-foot tomato stake and 36″ of 24″-wide nylon screening at your local hardware store. Cut the stake in half, sharpen one end of each now-36″ stake, and then staple or tack one end of the screening to the bottom of each stake. (You’ll want to leave about two inches of stake below the bottom of the screening.) You can probably make five kick screens for under $10.

Here’s a photo of MEMS students looking for bugs and other creatures on the kick screen they just used for collecting macros. Below the kick screen is a white plastic dish pan into which the students are transferring the insects.

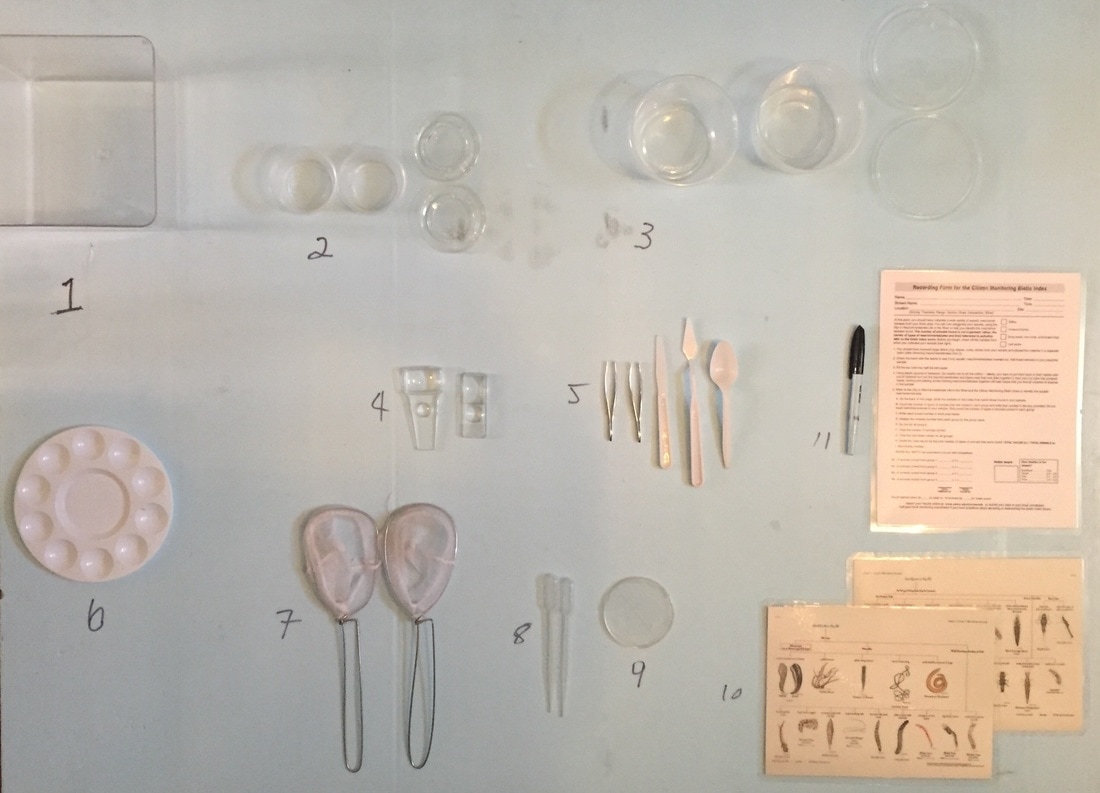

If you’re planning a macro collecting/classifying activity, you’ll want to assemble one or more collecting kits. If, like many teachers, you choose to break your students up into small groups of four or five kids, each under the supervision of an adult volunteer, you will need a kit for each group. So, you’ll have to acquire inexpensive materials.Here’s an example of a collecting kit.

None of these items was expensive, and all, with the possible exception of the pipettes, should be available locally.

I’ve laid out all but the “Dollar Store” wash basin on the foam board below.

Contents of collecting kit

- clear plastic box (for examining macros; this can also be used to flush macros from the kick screen into the wash basin)

- two small containers with covers (for saving distinguished specimens long enough to share with classmates; I got the containers for free from a fast-food restaurant)

- two larger containers (probably designed for a pint of potato salad) with covers (for examining and sharing marcos with others; obtained for free from a super market)

- small plastic magnifying glasses

- tools for transferring macros from kick screen/net to containers (shown here: two tweezers, two plastic artist pallet knives, one plastic spoon; artist pallet knives were purchased at a Michael’s arts and craft store)

- plastic artist paint tray (for sorting and separating different macro specimens from each other; also bought at Michael’s)

- two “guppy nets” (available wherever they sell baitfish, especially for ice fishing)

- two pipettes (for siphoning/picking up tiny macros; plastic eyedroppers could also be used for this purpose)

- small ruler with metric scale

- plastic-laminated macroinvertebrate identification charts (more on these later)

- plastic-laminated biotic index worksheet (also mentioned below) with “wet-erase” marker

Below is an example of one of the four macro identification charts that can be found in the “Insect identification charts” folder available on the TIC Google Docs site. (I’ve also provided a link to that folder.)

April 1, 2023

Temperature, videos, art. Guy Merolle’s phenology videos. The who and what of Release Day. But first ….

April Fools!

What’s the temp?

I suspect that western Rutland County, where I live, is milder that most of Vermont, but it certainly hasn’t been balmy lately. I went down to the Castleton River this afternoon. It was high and discolored but not muddy. Two days ago I threw my thermometer–attached to a light line, of course–off the bridge by the cemetery. When I pulled it up, I found the water was 39 degrees. That could change rapidly, however, in the next few days, especially if, as predicted, the temperature hits 64 degrees today.

Central Vermont Career Center

Ari Lattanzi, of CVCC, was concerned about her tank water, which she described as “greenish and cloudy.” She reached out to Clark Amadon, Robb Carter, and me. The consensus was (a) the cloudy water was due to too many nutrients, i.e., food and waste, in the tank, and the advice was siphon more and/or feed less and (b) the greenish tint of the water was likely algae caused by the tank water being exposed to too much light. The fix for that was to reduce the exposure to light. (Ari later confirmed that her tank sat close to grow lights. That will definitely do it.)

In spite of Ari’s worries, her water chemistry readings were good, and when she sent us a picture of her fish, we knew they were not only fine but great!

Fish art by Ludlow students

Lisa Marks, of Ludlow Elementary School, had her kids submit entries in the Fish and Wildlife Department Fish Art contest,

Here’s a slideshow of the artwork Lisa’s students submitted.

A few years ago, one of Lisa’s fourth graders produced a remarkable drawing of a brook trout. It was so impressive that I had questions: Did she start from an outline that Lisa provided? Did she take it home while she was working on it? Did she get any help? No, no, and no! She did it all in the classroom while Lisa’s aide watched in amazement. This girl has talent!

TIC videos

Two area teachers sent me short videos of their fish. This can give you an idea about what other classroom trout are looking like. The first video, by Barb Nauton at Wallingford Elementary School, was recorded on March 13; Maple Street School’s Suzanne Alfano recorded the second on March 18.

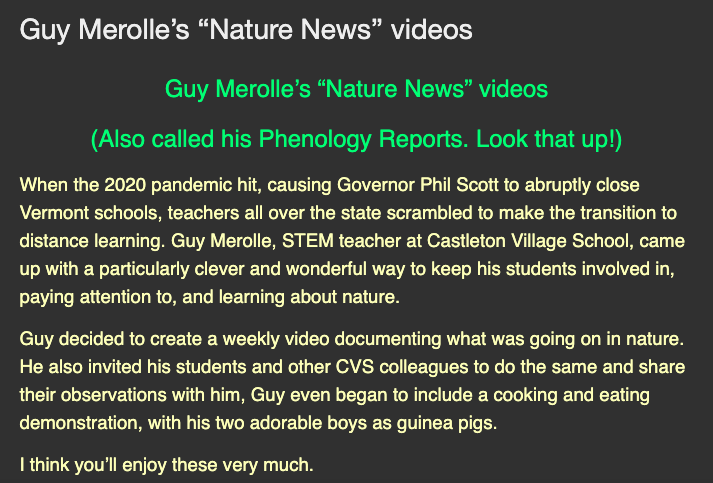

Guy Merolle’s “phenology” videos

I think we all want kids to spend more time in the outdoors. Guy Merolle, formerly of Castleton Village School, now at Fair Haven Union High School, found a great way to do that. He would record a video of the latest changes taking place in nature each week. He also challenged his students to find their own examples of how the woods and the fields were changing.

Click on this text block below to access Guy’s wonderful short videos (one follows the text box too).

The WHAT of Release Day

- take the temperature of the stream (presumably before you release your fish)

- test the stream’s water for pH, KH, ammonia, etc.

- collect and identify macroinvertebrates

- using data you gathered on various types of macros, calculate the biotic index of the stream

- assess the riparian zone

- inspect and classify the substrate embeddedness

- estimate the volume of the stream at a particular point

- estimate the speed of the stream

- play Macro Mayhem

- sing a trout song

- write trout haikus

- display your trout-square quilt

- sketch the stream

- eat trout-themed cake or cupcakes

And now, a Release Day video:

More RD videos can be found here.

The WHO of Release Day

- fellow school staff members

- parents and grandparents

- Vermont Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and U.S. Forest Service staff (especially for electro-fishing demonstrations)

- Trout Unlimited members

- Audubon Society members

- if you have one, the local “watershed group,” e.g., White River Partnership, Friends of the Winooski River, etc. (Review the list found here to see if there is a group in your area.)

- sportsmen’s groups, e.g., New Haven River Anglers, etc.

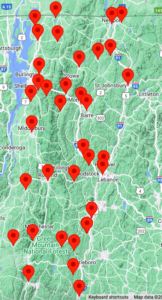

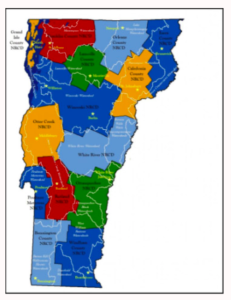

- the local “natural resources conservation district” (Click on the map below to go to the home page of the Vermont Association of Conservation Districts. Scroll down to the map and click on the district for your area. That should give you contact information.)

All across the state there are watershed groups. Are any of these rivers near your school? If so, the members of the local watershed group are very likely people who know a lot about area streams. Those folks would be great volunteers to recruit for your Release Day.

- Batten Kill

- Black River

- Connecticut River

- Deerfield River

- Mad River

- Hoosic River

- Huntington River

- Lewis Creek

- Missisquoi River

- New Haven River

- Ottauquechee River

- Rock River

- White River

- Winooski River

Click on the map below to get details on the watershed group in your area.

March 21, 2023

Trout Camp for kids! Introduction to fly fishing for women! The when and where of Release Day

Trout Camp!

If any of your students are both (a) becoming passionate about fly fishing for trout and (b) between the ages of 13 and 16, let them know about Trout Camp. This is a dynamite five-day program that will be held at Quimby Country Lodge in Averill, Vermont, from June 18 to June 22. Click on the license plate to go to the Trout Camp web site.

- Campers will be introduced to the basics of fly fishing through a series of fun and engaging outdoor activities. Participants will learn from some of Vermont’s most accomplished fly anglers and conservationists.

- Fly fishing skills covered will include casting, knot craft, fly selection, reading the water, presentation, and safe wading.

- Campers will learn about fish biology, fish habitat, and stream ecology as well as aquatic entomology.

- Other topics will include fishing etiquette and ethics, as well as conservation issues facing our cold water fisheries. In addition, campers will have the opportunity to participate in a local TU conservation project.

- Campers will have ample opportunity to test their newly acquired skills while fishing the upper Connecticut River and nearby ponds, hopefully catching lots of fish!

Helping an eager young person attend a program like this could be transformational and could spawn a lifelong interest in the outdoors in general and trout fishing in particular. Here’s a video filmed at last year’s Trout Camp and produced by TU member Ian Smith.

Intro to fly fishing for women!

It’s not just the kids who get to have fun. There’s a program for women too!

The weekend of May 20-21, 2023, is slated for the second annual Intro to Fly Fishing for Women program, held at wonderful Seyon Lodge in Groton, Vermont. (Click the image below to go to the program web site.)

The Lodge at Seyon is situated within the 27,000 acres of Groton State Forest. The setting allows guests to enjoy some of the most beautiful and undisturbed natural scenery in Vermont. All of this and fishing on Noyes Pond–Seyon spelled backward–for wild brook trout! The pond offers a remote setting that anglers appreciate as much for its peace and solitude as for the breeding ground it provides for native brook trout.

Registration starts in February 2023. (I’ve heard that spaces are going fast.)

Participants will learn about gear, fly casting techniques, aquatic entomology, knot tying, and proper fish handling.

The volunteer staff have great skills and experience and are looking forward to passing along a lifelong passion for the sport!

If you’re a woman and have any interest in fly fishing, consider giving this great program a try. It could change your life!

The when and where of Release Day. It’s not too soon to plan.

In the next blog I’ll address the who and what of Release Day planning, but for now we’ll tackle the when and where questions.

When?

Most schools schedule their Release Days for the last two weeks of May or the first two weeks of June. A few go earlier, but those four weeks tend to be a time when you can count on the weather: it won’t always be sunny and dry, but it probably won’t be too cold.

Depending on what you plan to do at your Release Day–more on this in my next post–you should probably also schedule a back-up rain date. It’s not that you and your students can’t have a very successful Release Day in the rain–I’ve been part of them, and they can be great–but a true downpour might “dampen” most people’s spirits, and raging torrents because of days of heavy rain could pose serious risks.

A few schools enjoy the privilege and opportunity of being able to walk to their release sites, but most schools transport students to Release Day using school busses. If that’s going to be the case for you, you may need to get your reservation in ASAP and perhaps even schedule your release around the availability of transportation.

A final consideration is the availability of volunteers. Most schools plan Release Days that include a variety of in-stream or stream-side fieldwork activities (that’s the what). In almost every case, it’s helpful if not necessary to enlist the help of parents, co-workers, Trout Unlimited members, or other community volunteers (they’re the who). You wouldn’t want to schedule your Release Day at a time when the volunteers you need can’t attend.

So, the takeaways:

- Book your busses early and, unless you plan to do a quick and simple Release Day,

- Schedule a back-up date.

What about where?

Depending on where your school is located, you may have several fabulous release site options close by or you may have no good options without traveling a distance.

What’s the perfect release site? I often describe it as “skinny water,” a small tributary brook that’s just big enough to support trout and the bugs that will sustain them but small enough so that nobody, not even your most over-eager young student, can get into trouble.

Here is my wish list of the ideal characteristics of a great release stream:

- a “safe” stream, ideally three-to-six feet wide with water not much deeper than eight or ten inches,

- close to a location where you can safely de-board students from school busses, preferably without having to cross a road,

- with adequate parking for the school bus(ses) and cars of volunteers,

- with easy access to the stream, that is, no steep banks,

- ideally with an “assembly area”–such as a cleared, level stream bank, meadow, or lawn–where you can meet before and after activities for such purposes as giving instructions, breaking into groups, reporting on what you’ve found or learned, celebrating with a special cake, etc.

- on public land or on private land that you’ve been given permission to use.

Below I’ve inserted a few pictures of streams that I consider terrific release sites. I took all these photos on March 26th a few years ago. Your local streams probably look different today.

When we get a heavy rain, because we live in an area that includes both mountains and valleys, water affects our brooks, streams, and rivers differently, depending on altitude.

At the outset of a heavy rain event, most waterways go largely unaffected. Gradually, however, mountain streams at the highest elevation will begin to swell. Water levels in the valley rivers, on the other hand, will initially remain unchanged. Over time, that response to the rain event will change. Soon, unless we’re experiencing a truly severe storm (think Irene), highland streams will return to their banks fairly quickly while rivers in the valleys continue to flow high and muddy and to overflow their banks for days. That means that on any given day, two locations for release sites might be ideal, one for dry-to-a moderate-rain-event conditions and one for when the storm has significantly altered water levels except in the mountains.

Finally, if you’re having trouble finding a good release location, ask for help, either from (a) stream-fishing-inclined parents or community members you know, (b) your area Trout Unlimited TIC liaison, or (c) me.

Good luck!

March 11, 2023

Almost all about swim-up. What’s happening?

Last Thursday, Dan “Rudi” Ruddell, our stalwart colleague at White River Partnership, reached out with some concerns about several schools he works with in the White River watershed.

A few schools are again experiencing high mortality right now, likely due primarily to lack of feeding response (apparent pinheads).

These teachers have tried moistened food with the turkey baster, light level adjustments with the insulation, tank has cycled and tank chemistry seems OK.

Not quite sure what else to suggest. Are others seeing similar right now? Any further suggestions?

Unfortunately, I couldn’t reply with encouraging news. It sounded to me that the schools so affected had for whatever reason “missed the swim-up.” That means that they probably didn’t happen to see the subtle signs of the swim-up stage and, therefore, didn’t provide food to the alevin at the right time.

Once that brief (maybe three- or four-day long) swim-up phase ends, you don’t get another chance. If you’ve missed the swim-up, your alevin typically never feed but just get skinnier and skinnier until they die. It’s very sad for all. (Sometimes a small number of alevin will, however, figure out eating.)

Here’s what that can look like:

Another cause of pinheads can be excessively cold water temperature. A few years ago, I asked the advice of Jeremy Whalen, supervisor of the Roxbury Fish Culture Station. Here’s what I learned:

Jeremy indicated that keeping the temperature too cold could also interfere with the swim-up process. He said that trout are not likely to eat well if the temperature is much below 50 degrees.

Coincidentally, while shopping at the Rutland Price Chopper on Friday, I saw Neshobe school teacher Kim Faber in one of the check-out lines. Of course, I had to ask Kim how her fish were doing. She said that they were great and that she thought they’d be swimming up soon. I asked her what the DI was. She said 81. Then I asked what the water temperature was. Kim replied that she’d been using the “cool and slow” protocol and that it was still in the low-40s. Oops! I urged her to raise it to at least 50 degrees.

Here’s another photo. This shows fish that are swimming up and feeding and others on the bottom of the breeder basket who appear to have become pinheads.

So how are your fish doing? Let me know and, as always, I love to receive photos and videos.

And then Bob Wible weighed in

Bob, former longtime TIC liaison for schools in the Champlain Valley region, may be our most experienced volunteer. Bob sent a series of questions to Rudi that, taken together, provide a lot of information on how to manage the swim-up process successfully.

Here are some of his questions:

- What temperature were the problem tanks when swim-up was expected (DI >/= 85)?

- Is the top cover off the tank after the DI gets to about 83 and stays off until DI=100?

- During swim-up, did the teachers feed their fish each day of the weekend?

- How long after DI=100 do the fry stay in the basket?

- What is the KH of those tanks?

- Is it a standard setup and are they doing anything unique or different?

- How often do they feed each day?

- Any extra cleaning being done around the tank during school break?

I have reordered some of Bob’s questions and used bold formatting on the first four. I’ll comment on each of these four separately.

Temperature. If the water temperature is much below 50, even if the DI is in that desired 85 to 93 degree range, there’s high likelihood that fish might not swim up.

Light. Along with temperature, light is a key trigger of feeding behavior.

Daily (or more frequent) feedings. When the fish are ready to start feeding, you cannot deny them. If some of them start feeding on Thursday or Friday and you don’t feed them over the weekend, you might interrupt the feeding response. When the DI is in that desired 85 to 93 degree range, is probably the only time you need to feed them over the weekend. Once they’ve been feeding consistently for a week or more, they can go a couple of days without being fed.

Don’t let them out of the basket too soon! The breeder basket is small–about five inches deep; a 55-gallon tank is big–21 inches top to bottom! Every year, some schools release their fish into the big, wide world of the tank too soon. Fry that easily see and respond to provided food floating a few inches above them may have much more difficulty noticing food floating on the surface when it’s 20 inches away. When in doubt, keep your babies in the playpen longer, at least several weeks after they’ve all been feeding eagerly. If you’re really itching to let them loose in the tank, try it first with just a handful of fry and see how they do. If they eat well in the big tank, then perhaps their siblings are ready to join them out there. If, however, some or all of those released aren’t reliable eaters when they’re in the big tank, try to net them and return them to the breeder basket for another couple of weeks.

Thanks, Bob, for sharing your experience with us!

And now, a short video from BRMS

Chuck Goller, one of our dependable TIC volunteers in Chittenden County, forwarded a video that Browns River Middle School teacher Jeff Warren sent him. Those fish look healthy and beautiful, Jeff! Keep up the good work.

Finally, we celebrate an anniversary.

In two days we will celebrate the third anniversary of March 13, 2020, the day Governor Scott abruptly closed Vermont schools because of the pandemic with 24 hours notice. Those of us involved in Vermont’s TIC program three years ago will long remember the chaos and disruption that the governor’s announcement caused.

And I will never forget the valiant efforts and creativity that Vermont’s TIC family invested in responding to that crisis. Those of you who went through it know the story.

- Some of you took your still-immature fry with you as you left school that day and found a convenient brook to deposit them in.

- Others got approval to continue visiting and caring for your fish.

- Still others convinced employees with school access–principal, custodian, etc.–to take on the feeding and tank maintenance jobs.

- A few of you tackled the enormous project of moving your tank and its occupants to your homes.

- When teachers didn’t have space for a tank, friends and parents agreed to “babysit” the trout in their homes.

- And then there was all you did, in spite of this huge disruption and the extra duties of remote learning, to keep the program running for your students.

- You put “trout cams” on your fish

- You filmed yourself releasing fry

- You created clever and educational videos

- You challenged your students to send you photos and videos of the changes they observed taking place in nature that spring

- Finally, there was the support that we got from the Leahy ECHO Center and the Montshire Museum, both of whom agreed to set up online TIC tanks for you and your students to observe and learn from.

What an impressive, heroic effort! You people are wonderful! Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Take a bow. Pat yourself on the back–heartily. And do something special on 3/13/23 to celebrate our collective accomplishment.

February 4, 2023

Some birth defects and fish disease. National TIC/SIC quilt project. Kids fish art contest reminder.

Some of the things that can go wrong when you raise about 10,000 salmonids

Anna Kovaliv, of Camels Hump Middle school, sent me this message Tuesday.

Hi Joe,We had a sad, weird thing happen today! We had one fish that was c-shaped–almost like its yolk sac was attached too close to its chin and to its tail. Today… the sac popped open! My kids were really sad (we had it in a separate basket because it wasn’t growing as strong as the others and two of my kids named it Hero). Here is what it looked like today. The poor thing was still trying to move and breathe but it wasn’t long for this world.

Hello Clark and Joe,

the yolk sac appeared to be growing. On closer inspection, we saw what appeared to be a sac within the sac. The kids thought that maybe it has two sacs, it has an infection, or maybe it has cancer and has a tumor. On closer inspection, we could see blood inside the sac.

A very good example of “Blue Sac.” Agree – best to euthanize fish like this.

Tom

Here’s a bit of information about blue sac disease.

Hello TIC and SIC Teachers,

Hard to believe, but it’s already February, which means the sign up period is open for the nationally beloved Salmon & Trout Quilt Square Project! This year’s theme is the Wonderful World of Water!A big thanks to Vermont TIC teacher Tiffany Bates and TU’s NYC TIC Field Educator Miranda Velarde for stepping up to help with this year’s project.The Trout and Salmon Quilt Square Project is a hands-on STEAM activity through which students reflect on their STEM-learning during S/TIC by creating a fabric quilt square and writing a letter to another classroom in a different part of the United States. It is a reflection and sharing of their science learning around a theme as well as a geographical and cultural exchange through writing and mailing letters.Sign ups are open now through Friday, February 17. Teachers can sign up via our Quilt Project google formAfter signing up, teachers will receive a confirmation email and instructions from Tiffany, Miranda, and me the week of 2/20. I have attached the instructionshere but TEACHERS MUST SIGN UP USING THE GOOGLE FORM TO BE INCLUDED IN THE MAILING LIST. If you do not sign up, other classrooms will not know how to send the squares to you.For more information about this hands-on, STEAM project, please see the attached instructions. I hope you can join us! Please reach out with questions.Best,Franklin (fjtate89@gmail.com)

If you want to participate, don’t miss that February 17 deadline!

Art contest

Speaking of deadlines, remember the fish art contest I told you about? Well the deadline for that is coming up on February 28. If you want to give your students the opportunity to participate, don’t miss it! (Click on the image below to access the Fish and Wildlife Department’s web site for the contest.)

January 30, 2023

Swim-up starts at some W&F schools. Lee Simard presentation. PIX from Shrewsbury.

Let the swim-up begin!

On Friday, a new TIC teacher e-mailed several questions about swim-up and provided some information about her tank. Here are some of the points we exchanged:

- TEACHER: “The alevin look very close to swimming up, as their egg sacs are all but gone. Since we are at a weekend, should I put the baskets on the bottom of the tank in case some swim up over the weekend?”

- JOE: “What’s your DI and what’s your tank’s temperature?”

- TEACHER: “Tank temp is 55 and DI is 82.71.

- JOE: “So swim-up is imminent. Keep the front and top foam off during the day. Assuming your thermometer is accurate, you can expect them to start swimming up between tomorrow and Thursday. [I determined that by plugging the teacher’s numbers into the ‘2022 Temp and DI record and swim-up calculator’ file,] Even after it appears the yolk sac is used up, there’s often some left. The manual has some photos. [Page 83 & 84.] Don’t drop the basket! You’ll want to keep them in the basket for several more weeks. They have to be feeding actively for at least a couple of weeks before you let them out of the basket.”

- TEACHER: “Should I start feeding on Monday or wait until 25% have swum up?”

- JOE: “Observe their behavior. At first, they probably won’t swim up more than just a little bit, but yes, when a number of them are exhibiting that behavior, drop a tiny bit of food into the breeder basket. If none of the alevin give it any attention, see if you can scoop out the food sitting on the surface.”

IMPORTANT!

The teacher who emailed me with these questions (and with that DI number of 82.71) has clearly been using the “warm and fast” temperature protocol. Teachers who have had their tanks at significantly cooler temperatures may be many weeks from swim-up. If you’ve been keeping track of temperature and plugging it into the spreadsheet every day, including breaks and weekends, you should know when to expect swim-up.

Page 84 of the VTTIC Manual contains a link to this YouTube video, which can be helpful in learning what swim-up looks like. One correction: one of the slides says it takes one or two weeks for the yolk sac to be absorbed. I’ve never known it to happen that quickly!

Lee Simard on stocking

If you missed the presentation by fisheries biologist Lee Simard on the stocking practices and policies of the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, you can watch it here.

Shrewsbury report

I got an e-mail and some photos recently from Sabrina McDonough at Shrewsbury Mountain School. The day the eggs were meant to be delivered, Tinmouth Elementary School teacher Jenn Tifft discovered a problem with her filter, so Sabrina and her students “babysat” Jenn’s eggs for several days. Here’s a portion of Sabrina’s e-mail.

I’ve included some of the photos from our work so far this year. We did begin with our annual counting of the eggs (through close up images) and even counted Jenn‘s for her. Unfortunately, we did have about 4 opaque eggs at the start and a white growth on 2 of them. After that initial “set back” all has been going well. Jenn‘s alevin were collected last week and I have transferred some of our alevin to the 2nd breeder basket. We are beginning a unit of study on water as a natural resource and the interaction of Earth’s spheres so our work with the trout will become a focus during our lessons.Have a great week-Sabrina

I’m intrigued by Sabrina’s last sentence, “We are beginning a unit of study on water as a natural resource and the interaction of Earth’s spheres so our work with the trout will become a focus during our lessons.”

Let me know how you’re connecting trout and TIC to your curriculum and your students’ learning.

And send pictures and videos of what’s going on in your classroom!

January 17, 2023

Egg deliveries

Between January 4 and January 11, all across the state, Trout Unlimited volunteers and their friends delivered eggs to almost 90 Vermont classrooms. Weather cooperated, so we didn’t have to reschedule any of the planned deliveries. Needless to say, teachers and students were excited to receive their new round little classmates.

Here are photos Dan “Rudi” Ruddell, of the White River Partnership, sent me of deliveries he and others made to schools in the Greater Upper Valley TU Chapter area. Deliveries were made to FBUD-Chelsea, FBUD-Tunbridge, South Royalton Elementary School, Waits River Valley School, and White River Valley Middle School.

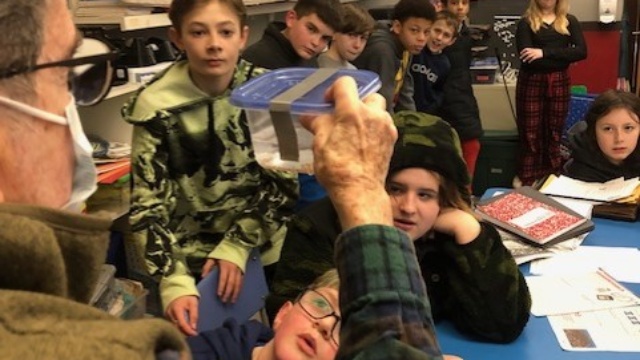

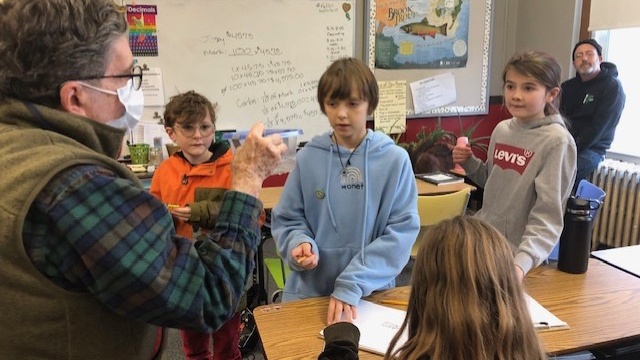

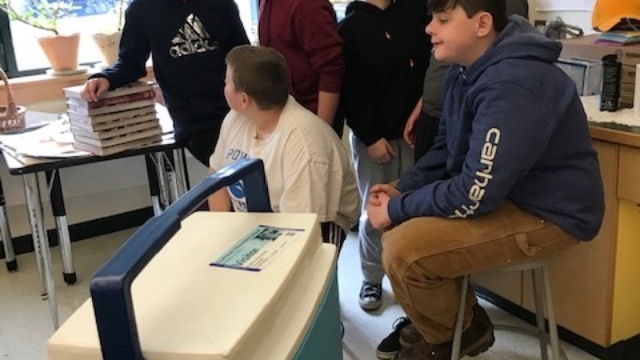

Barry Mayer and Bonnie Daley delivered eggs to the three most southern schools in Southwestern Vermont TU Chapter’s region. They visited Mount Anthony Union Middle School, Shaftsbury Elementary School, and the Village School of North Bennington.

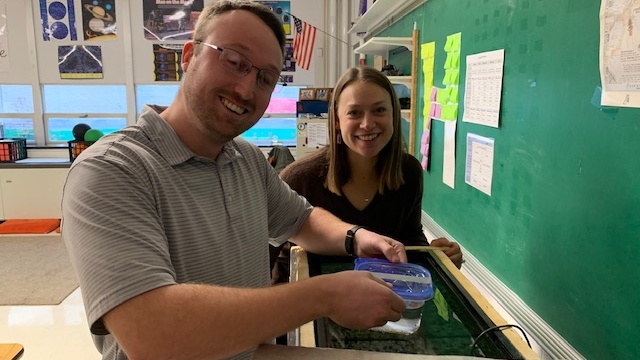

I got these great photos from Joe Kraus, who made deliveries to Rutland Middle School, Rutland Town School, and West Rutland School.

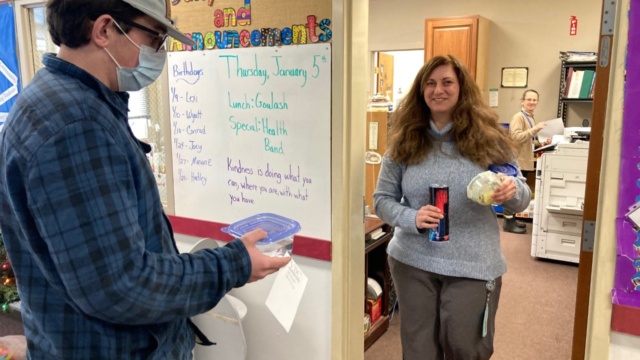

And here are some of my photos. I was fortunate to have my UVM freshman grandson Calvin join me both on the trip to the Roxbury hatchery and as we delivered eggs to Neshobe Elementary School, Ludlow Elementary School, and Shrewsbury Mountain School. Then, on the last leg, I delivered eggs to Poultney Elementary School, and Fair Haven Union Middle School. Finally, I brought Benson Village School’s eggs to Keith Piontek at West Rutland School for a week or two of egg babysitting..

Remove shells and dead eggs

The first few weeks of the TIC program are usually pretty quiet, but there are a couple of important maintenance tasks teachers and students need to perform, Almost certainly some of the eggs you’ve received will die. In contrast to healthy, viable eggs, which are translucent and orangey, the dead/dying eggs turn white as in this photo.

It’s critical that you remove and discard those, or they will decay and lead to development of fungus or mold. The best way to do this is to suck them up with your turkey baster.

The same is true of the egg shells left behind after your alevin have hatched. These too need to be removed.

Water Changes

Water changes are one of the most important ways to manage water chemistry. Water changes, properly done, also allow us to siphon out waste that would otherwise, by its decomposition, spike ammonia and/or nitrite numbers.

Let’s start with the basic water change. At this point in the TIC season, you are not feeding your fish nor are they defecating, so there should be no solid waste in the tank that needs to be removed. However, I hear from teachers who still have elevated levels of ammonia or, especially, nitrite. This is probably due to an incomplete pre-cycling process and is a concern. When the pre-cycling process is successful, it ends with ammonia and nitrite at 0.0 ppm. Only nitrate is elevated, and this is not a problem (more about this later). But if the pre-cycling process doesn’t make it all the way through to the end, your tank may have ammonia or nitrite readings significantly above 1 ppm.

These require water changes, but how much water should you remove and replace (with water treated with NovAqua Plus, of course)? The answer is found in simple math—proportions and ratios to be specific. Let’s look at an example.

Say you have a 55-gallon tank, as many of you do, and say your nitrite is 3 ppm. If you want to get that nitrite below 1 ppm, how much water do you have to remove and replace? By removing and replacing tank water you are endeavoring to dilute the nitrite. If you replaced a third of the water in your tank—18.3 gallons of a 55-gallon tank—with nitrite-free tap water, what will your post-water-change nitrite level be? I’m predicting 2 ppm. You’ve still got 37.7 gallons of 3 ppm nitrite water, and you’ve diluted that with only 18 gallons of 0 ppm nitrite water.

Similarly, if you replaced half of your water, I’d expect your post-water-change tank water to have a nitrite level of 1.5. Only if you remove and replace two-thirds of your water should you expect your nitrite to drop to 1 ppm.

So this is an excellent, real-life way for your students to learn about fractions, ratios, and proportions.

A two-bucket classroom

To do water changes efficiently, you’ll want to have two uncontaminated five-gallon buckets. Normally you’d fill one with replacement water that you treated with NovAqua Plus to neutralize chlorine and other toxic metals. The other bucket is to catch the water you’re removing, usually with a siphon hose or tube. (Later in the season, this second bucket will also reveal how dirty your tank is, especially if you swirl the water vigorously, which provides a demonstration of centripetal force.)

Page 27 of the VTTIC Manual describes how to perform water changes.

Here’s a YouTube video about how to use your siphon to remove waste from your tank.

Nitrate levels

The above post about water changes is important especially because levels of ammonia or nitrite above 1 ppm can be very dangerous to your fish. We worry a lot less about nitrate, but over the years many teachers have performed water changes to lower nitrate levels. In fact, the chart on page 32 of the Manual seems to imply that you should do a water change when nitrate readings reach 45 ppm.

I recently received an interesting e-mail on the subject of “high nitrate” from one of the members of the national TIC/SIC discussion group. This has me rethinking our past “conventional wisdom” about nitrate management.

When dealing with your classroom teachers, please ask them what they mean by “high nitrates.” I had a teacher contact me this week who was concerned about “high nitrate” levels of 20 ppm. I assured them that a nitrate level of 20 ppm is considered low and is a non-issue for the trout in our closed-system, recirculating aquariums. The API test kits that most of us use are NOT accurate at 0-20 ppm levels of nitrate. More costly test kits are required to accurately measure nitrate at those low levels. EPA drinking water standards call for tap water levels of 10 ppm or less but in actual practice, especially in areas that use well water, we find readings of 20 ppm regularly.

Therefore, if your teacher is using tap water with a baseline level of 10-20 ppm for water changes, they never will achieve a reading of 0 ppm.

Research from the Journal of Aquacultural Engineering has shown no statistically significant difference between trout raised in 0 ppm nitrate levels versus those raised in 100 ppm levels of nitrate.

That said, I have had nitrate levels of 600 ppm on a test aquarium with no harm to my trout. Commercial closed system, recirculating trout hatcheries, recommend levels of less than 1000 ppm of nitrate…. In other words, DON’T WORRY ABOUT NITRATE LEVELS!

Troutfully yours,

Dr. Rod Berkey

AZTU, Zane Grey Chapter

December 31, 2022

Spawning

Eggs will be hitting the road soon! Except for the handful of Vermont schools that raise landlocked Atlantic salmon, all the rest of you raise brook trout, Vermont’s state fish. Brook trout eggs will in the next few days be picked up at the Roxbury Fish Culture Station, where they’ve been under the expert care of Jeremy Whalen and his staff. But that’s not where they began their fishy journey. You might say that they were “conceived” at the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife’s “broodstock facility” in Salisbury, Vermont. This kind of facility is a place where the F&W department keeps its “broodstock,” the larger males and females they use for spawning. To produce eggs for the TIC program, Salisbury hatchery staff separately collect eggs from mature female trout and “milt,” or sperm, from mature males. These critical ingredients are then mixed together. That’s when fertilization takes place, and for our brook trout eggs, it occurred on November 3, 2022. Once fertilized, the eggs were transferred to the Roxbury hatchery.

Here’s a video of a presentation by Roxbury hatchery manager Jeremy Whalen on the subjects of the spawning process and triploids and how they are created.

And here’s another YouTube video about the hatchery spawning process in the state of Pennsylvania.

Triploids

For the last few years, the Fish and Wildlife Department has been producing “triploid” eggs for our program and for much of the stocking the department does. Triploid eggs are eggs that have been modified to render them sterile. As a result, these fish can’t interbreed with native fish. Why do you think the department would want to do that?

Here’s a link to a presentation by Roxbury hatchery manager Jeremy Whalen about spawning and triploids and how they’re created. This is a rich topic for research, discussion, and debate. Dive into it! …. https://youtu.be/rzOtgH7PIf8

Reducing cannibalism through technology

I participate in a national group that allows TIC and Salmon in the Classroom teachers and coordinators to share both challenges and successes. Recently, a Colorado 8th grade teacher reported on how her students responded to cannibalism they observed in their tank. Cannibalism typically results when a significant size gap develops between the smallest and the largest fish in an aquarium. When they’re hungry, big fish have no compunctions about eating their siblings. (Below I’ve provided a picture of cannibalism in process.) Cannibalism sometimes indicates that you are under-feeding your fish. (On the other hand, we discourage overfeeding because it can result in too much organic waste, which, during its decomposition, can produce high levels of ammonia and nitrite.) When your fish are feeding, you’ll notice that some fish are more aggressive than others —and more successful at gobbling up the food you provide. The aggressive fish will swim up to the surface as soon as you add food and will quickly eat most of what you’ve put in the tank. The less aggressive, more timid, fish typically hang out near the bottom, hoping to get a chance at whatever leftovers drift down that far.

1. Aside from feeding your fish more, which has its risks, one way to help the less aggressive fish keep up with their rapidly developing bigger siblings is to soak some food in water to make it water-logged and then to siphon it up, using your turkey baster, and inject it towards the bottom of the tank. Some teachers even add tubing to their basters to more effectively shoot it down to the bottom of the tank.

2. A second strategy is to net the largest and most aggressive fish, those particularly inclined to cannibalism, and put them back into one of the breeder baskets. We call this the “time-out room.” (Do schools still use that terminology?) This would give the smaller fish the chance to catch up in their development, especially if you didn’t provide a lot of food to the already-bigger fish.

All of these developments create wonderful opportunities to discuss what happens in nature, including the principle of “survival of the fittest.” But a third strategy is contained in an e-mail from Kellina Gilbreth.

Kellina is a middle school teacher in the Cheyenne Mountain School District in the southwest corner of Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Here’s what she wrote.

Hey All, Wanted to share a little project I have my middle school students working on before we leave for winter break. A few weeks ago I noticed that some of the fish were dramatically larger than the others. I let the folks at Trout Unlimited know, and they told me there is likely cannibalism going on. Sure enough, one Friday before I left the school, I noticed a big fish had a little fish sticking out of its mouth! Cannibalism confirmed. (See Kellina’s photo below.)

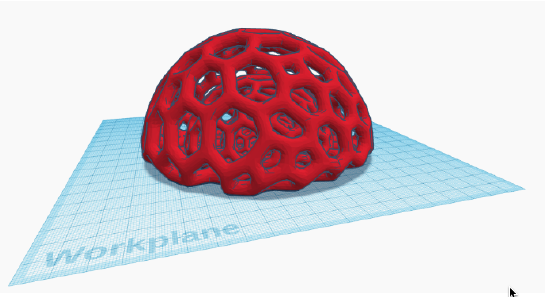

My 8th grade classes were a few days ahead of the other 8th graders, so I decided to try an engineering project that Trout Unlimited had suggested at one. of the past meetings. Earlier this week my kids researched and created 3D designs for fish shelters, and I will be printing some of them with our school’s 3D printer. I have attached screenshots of the top 3 most voted for designs. Hopefully the little fish will use the shelters over the break and avoid getting eaten by the big fish!

The students are super excited to be able to help out the little fish. Hopefully we will find that one (or more!) of the designs are a success!

Here’s one of the designs Kellina’s students produced.

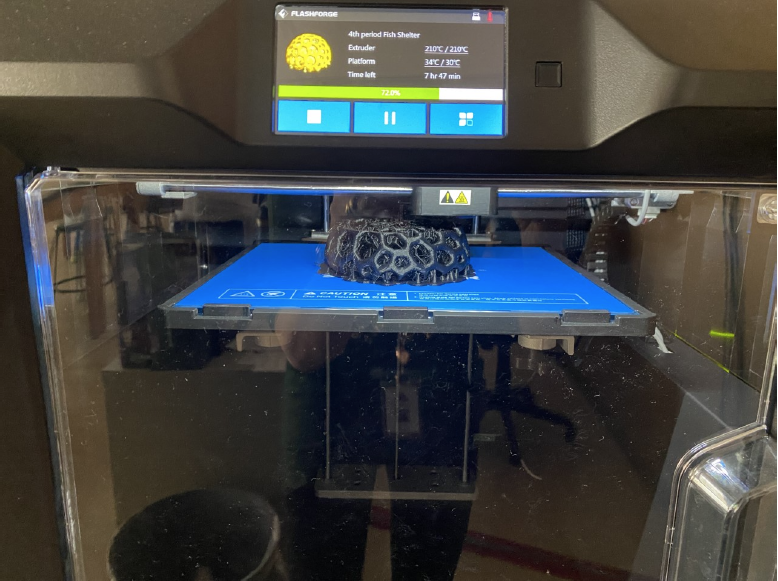

Here is a picture and video ( IMG_1354.MOV) of the 3D printer building Design 3 (the red dome shown above):

Finally, here is the link where you can make a copy of the project description that I gave to my kids:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/ 1zfKGbTl8WC1L0u7LGi57dJ0kxIet6oTK6xxXho7M7YU/copy

Kellina provided some additional tips:

1) If you use PLA filament, be sure to set the infill to 100%. PLA has a density of 1.24 g/cc, and so it is only a little heavier than water. If you set the infill to anything less than 100%, it is likely that your designs will float instead of sink to the bottom of the aquarium. Of course, if you use another type of filament, check that it is safe to use with aquariums and that its density is greater than 1 g/cc.

2) The fish don’t seem to like light colored shelters. We had both white and black filament, and the fish appear to favor the shelters that are printed in black PLA. 3) Be sure to wash and rinse the 3D design in tank water before adding it to the aquarium!

Kellina, you rock! Thanks so much for sharing your creative work with us.

PS: It worked! The small fish began to hang out in the shelters Kellina’s students created for them.

Here’s a picture of Kellina’s school. A little different from most Vermont schools, huh?

Quilt project

Finally, think about all your kids could learn if they participated in the national TIC/SIC quilt project?

The national quilt project is an opportunity, among other things, for students to reflect on where they live and also learn about where other TIC students live. Think about signing up when the project is announced.

December 8, 2022

Hanna Galinat, of The Riverside School, sent me this great photo of some of her proud, bold, happy, be-hatted girls setting up their tank. I love it!

Except for her lovely smile, the girl in the yellow hat reminds me of the Fearless Girl sculpture that has faced down the Wall Street bull.

Send me more.

Pre-cycling

Most teachers will have begun the pre-cycling process. Make sure you’re using a tank heater and have it set at 75 degrees. Next Monday we’ll offer a special Zoom meeting at 4:00 pm to discuss any issues that have arisen about pre-cycling. Prior to the meeting, you should review Chapter 4. Also make sure you read the directions for use of Dr. Tim’s ammonium chloride. (In relaying some details of an exchange he had with the real Dr. Tim, our Maryland TIC friend Chuck Dinkel reported that over the years the amount of ammonium chloride to be added per each gallon has changed.) And it’d be best to have your water chemistry and temperature data on hand. We’ll also talk about temperature management as it relates to determining when “swim-up” occurs. More about that below.

I’ll send out the Zoom invitation around 3:45 that day.

Fish art contest

Amy Clapp, of Salisbury Community School, let me know that Vermont’s Fish & Wildlife Department is sponsoring a fish art contest for kids in grades K through 12. Thanks, Amy! There are four age categories for entries. Students must choose a fish species—I assume most of our kids will choose either brook trout or Atlantic salmon—and draw or paint an illustration of it. Kids in 4th grade or higher also need to research their chosen species and write a one-page “creative writing essay.” Kindergarten through 3rd grade students don’t have to do any research or write an essay. Three prizes will be awarded in each age category. The deadline for submissions is February 28, 2023. Click on the image below to go the F&W page on the contest.

Water temperature options prior to swim-up

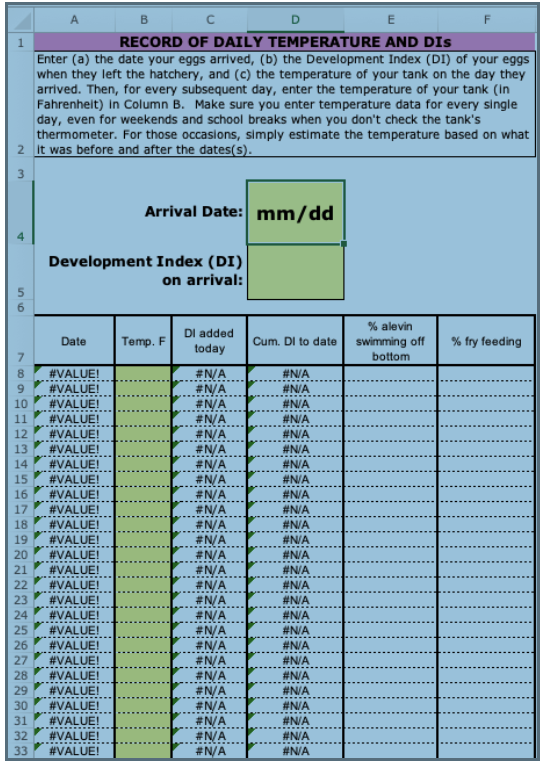

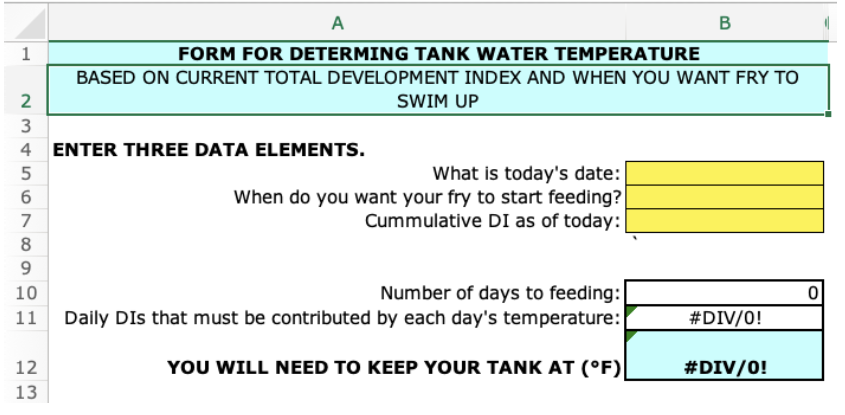

As we’ve often discussed, up to a point, the rate at which trout develop is directly related to the temperature of the water. And that applies to trout eggs as well and to the alevin (AL-a-vin) stage, after they’ve hatched but before they start feeding, when they’re kind of like tadpoles. The challenge is that there is a brief few days when they’re ready to eat and they need to be fed. This is usually when the cumulative Development Index—a measure of development based on temperature—is between 85 and 93. If you happen to be away from your classroom during that period or aren’t paying close attention, you may not notice the subtle signs that indicate they’re looking for food. In that case you might “miss the swim-up.” (See Appendices D and H.) If you do, you’re probably going to lose a lot of fish. They’ll live for a few additional weeks but get skinnier and skinnier, and then you’ll start finding them dead on the bottom of the tank. It’s tragic. We all get very sad: you, I, your students, maybe even the custodian. So to try to avoid this development, we’ve created some tools to help you figure out when your fish are ready to swim up, that is, to be fed. They are two Excel worksheets in the same workbook, one (worksheet “B. Temp. entry and DI record”) will reveal when your fish are approaching the swim-up stage, the other (worksheet “C. Swim-up calculator”) allows you to choose the date when you want them to swim up and will tell you the temperature you need to keep your tank at in order to achieve that.

Using the “Temp. Entry and DI record” worksheet Here’s a screenshot of the “B. Temp. Entry and DI record” worksheet.

THIS IS IMPORTANT Even if you choose the Swim-up calculator approach, you must continue to record the temperature of your tank’s water every day! “You don’t mean the weekend, do you?” Yes, I do. I don’t expect you to visit your tank on the weekend, but you need to guess, estimate, or, as mathematicians would say, interpolate to fill in weekend and school break temperature numbers. Regardless of your methodology, make sure you enter temperature data for seven days of every week. There have been instances in the past when a teacher who had set their temperature based on the swim-up calculator discovered that that method wasn’t going to work. They might have had a problem with their chiller or perhaps they learned that they would have to be away from school during the period when they wanted swim-up to occur because of conference or a family or medical leave. If they have been recording daily temperature values, they can always change the plan. If they haven’t been, they’re kind of stuck.

Here’s a link to a Google Docs folder that contains three Excel files. (If you lose this link, you can also find them in the 2022-2023 TIC data sheets folder in the Google Docs collection.) Read the instructions (Tab A) and then click on Tab B. This worksheet is where you will enter (a) the date on which your eggs arrived, (b) the cumulative DI value (Development Index) when your eggs left the hatchery, and (c) your daily temperature data. But even before your eggs arrive, you can use the “Temp. entry and DI record” spreadsheet to model various temperature scenarios. That’s what I do. I estimate when the eggs are likely to be delivered, say, January 9, 2023. (The plan is to deliver eggs during the week of 1/9/23.) Then I guess what the cumulative DI might be when the eggs leave the hatchery that day, say, 44. Then I can fool around—engaging in several “what if” hypotheses—to see when eggs would be ready to swim up. You can do this too. When you’re done with each scenario, exit, quit, or close out of the spreadsheet without saving it (unless you want to give it a new name). Here are two examples of options I pursued using the modeling approach.

Temperature Protocol Scenarios for Predicting Swim-up

#1 Warm and Fast

If

1. Eggs arrive on 1/9

2. DI on that day is 44

3. Tank temperature is 48 F. on 1/9

4. Tank temperature is 52 F. on 1/10

5. Tank temperature is 55 F. on 1/11

6. Tank temperature stays at 55 F.

Then

1. DI hits 85.91 on 2/3

2. DI hits 92.78 on 2/7

3. DI hits 99.65 on 2/11

#2 Cool and Slow

If

1. Eggs arrive on 1/9

2. DI on that day is 44

3. Tank temperature remains at 44 degrees through 3/5

4. Tank temperature is raised to 47 F. on 3/6

5. Tank temperature is raised to 50 F. on 3/7

6. Tank temperature is raised to 53 F. on 3/8

7. Tank temperature is raised to 55 F. on 3/9

Then

1. DI hits 84.98 on 3/8

2. DI hits 93.77 on 3/11

3. DI hits 100.64 on 3/15

So the warm and fast approach should get your fish feeding well before most schools have their winter breaks (either starting 2/20 or starting 2/27). Using the cool and slow method should mean that your fish start feeding after the later breaks (which end 3/6).

Using the “C. Swim-up calculator” worksheet This form is very easy to use. Just fill in the three yellow cells and hit “return.” Voila!

So, this should prepare you for setting your tank’s temperature come January. If you can, join us on Zoom at 4:00 pm Monday. In the meantime, here’s one of the ornaments my wife put on our tree three days ago.

November 28, 2022

Countdown to pre-cycling, Rod & Reel Sweepstakes, answers to some of Joe’s questions, dams!, reminder about first Zoom meeting

Pre-cycling

In the last blog I challenged teachers to meet the (slightly arbitrary) deadline of Thanksgiving as the annual deadline for having TIC tanks set up. Now we move on to the countdown clock for pre-cycling. Again, somewhat arbitrarily, we’ve establish the first Monday of December as the point at which to start the pre-cycling process. That’s just a week away! Read Chapter 4, read Chapter 4!

Did any of you notice the mistake or at least omission I made in my last blog with regard to pre-cycling? (There’s extra credit if you did.) I mentioned running your filter, aerator, and tank heater and keeping the water temperature at 75 degrees. I mentioned Dr. Tim’s ammonium chloride and the importance of water testing, but I left something out. Nite-Out II, which contains the good bacteria that are the heart of the biological filter so essential to keeping your tank and its fish healthy. My bad!!

Click on the image to the left to read the product description for Nite-Out II and how it works.

Pre-cycling can be a tricky business. There are a number of things that can go wrong. Here’s a partial list:

- maybe you’re not seeing the ammonia and nitrite readings that you’ve been told to expect

- water temp might be too low

- KH might be too low

- pH might be too high or too low

- Nite-Out II might be too old, have frozen during transport, or been stored in a way that killed the bacteria

But by starting early, there’s time to trouble-shoot these issues and still let you complete the pre-cycling process successfully. For that we need–tada!–PRE-CYCLING CONFIDENTIAL! (If you listen to public radio as I do, last week you may have heard an annual call-in program called Turkey Confidential.)

In a similar way, our head scientist, Robb Cramer, answers all pre-cycling questions (with minimal help from the rest of us volunteers). So, once you get the process started, think of him. Robb will be part of the Zoom meeting we have at 4:00 pm on Monday, December 12, but keep his e-mail address, rcramerjr@icloud.com, on the digital equivalent of speed dial.

Want an Orvis rod and reel? TIC fundraising “sweepstakes”!

A generous friend gave us an Orvis Recon rod (8’6″, 5-weight) and an Access Mid-Arbor reel (both new, with a combined value of $753) for the benefit of the TIC program.

Our volunteers conferred and decided the best use of this wonderful gift would be as the prize for an online sweepstakes that opened this morning and closes at midnight, December 24. All money raised will go towards a fund for purchasing TIC equipment for schools.

So, (1) if you need/want new equipment or (2) know someone who would appreciate such a gift or (3) just want to support the program so it can help Vermont schools eager to join TIC, enter the sweepstakes. You can buy tickets or make a donation at the link below. Remember, tomorrow’s Giving Tuesday! I’ll let you know how we do.

https://go.tulocalevents.org/vttic/

Some questions answered, at least partially

In the November 15 blog, I challenged teachers to have their students, depending on age, answer some of nine questions. (There will be more!)

The second question was, “How did the Europeans’ and the Native Americans’ attitudes toward the natural environment differ?” Well, Thanksgiving season is the perfect time to be considering that question. (Have you and your students discussed the myths and realities of America’s Thanksgiving story?)

Here’s a Washington Post article that focuses on “The Day Before America,” a book written by William MacLeish. In that piece, “MacLeish gives moderately good marks to the way most tribes interacted with the flora and fauna around them.” Speaking of the Archaic period, 3,000 to 10,000 years ago, MacLeish described it as a time when the Native Americans lived in closest harmony with their environment. He called the way of life of indigenous peoples as “perhaps the most sustainable that humans have developed so far.”

The Washington Post article goes on to say, “The religious beliefs and traditions of many tribes encouraged the view that humans were part of the natural world, rather than its masters.” It also describes, however, less laudatory practices: “In the Northeast they burned forests to force out elk and deer” and “created elaborate devices to drive herds of white-tailed deer into enclosures in the forest, where they were slaughtered.” It concludes with: “However brutal, such acts pale in comparison to the assaults Europeans would later launch on the continent’s resources. The beaver population was among the first to suffer. French and Dutch traders took 30,000 beaver pelts in 1620 and almost 300,000 in 1690.” The forests were also early casualties. After the arrival of settlers, MacLeish concludes, “the Midwest went bald in a human lifetime.”

Here’s an interesting Kahn Academy presentation about some of the differences between European and Native Americans. This piece, also from the Kahn Academy, describes the environmental and health effects of colonization.

Ask your students what they know about how Europeans regarded nature. How do present day European-Americans view nature? How do your students of European ancestry view nature?Are there Native American students in your class? How about students from other cultures. How do they view nature and what’s their understanding of how their ancestors viewed nature?

[slideshow_deploy id=’1684′]

Question number nine: On the temperature sensitivity of Vermont’s three trout species